THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 5

Fyerool Darma: destructing and reconstructing regional history

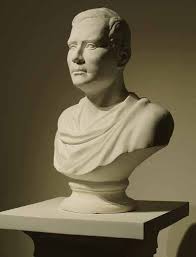

Fyerool Darma’s world is black and white, sleek and genuine; conceptual yet tied to the peculiarity of materials. If you were in Singapore at the beginning of 2017, you couldn’t help encountering his work everywhere – in very different sectors of the art world. At Art Stage Singapore 2017, he was part of the Yeo Workshop booth with his works ‘After Babelfish (of Shank series)’ and ‘Portrait No. 11 (Puan Saleha, Zaliha or Salihat)’. We saw him performing in the art space Objectifs for the collective show ‘Fantasy Islands’. And if that wasn’t enough, at the Singapore Biennale you can also encounter his work ‘The Most Mild Mannered Man’ – a bust of Sir Stamford Raffles and a bustless pedestal inscribed with the name of Sultan Hussein. His interest in bridging the memory-deprived Singapore of today with the wider history of the region and the many possible narratives that have shaped the island’s past, and continue to shape the island’s future.

“Growing up in Singapore, we had a lot of influences from abroad, including a western perspective on art. All these things are boiling in a pot waiting for you to do any dish you want,” explained Fyerool. “For us Singaporeans, it is very difficult to distinguish what is east and what is west. We understand both, and see how in this country they are entangled.”

On the internet, you could still find images of the artist’s old surrealist-style paintings. His early work was inspired by the book ‘Little Nude Boy’ by Federico Garcia Lorca and talked about individual oppression. I asked Fyerool if I could see them, but he said it was impossible; he burned them all. “I wasn’t attached to the work, as I felt I wasn’t being honest with myself. I was producing this imaginary over and over again and I couldn’t find something that would relate with society. Only later I realised this action was like erasing a part of my past self”, he observed. “By destroying your work, you are also contributing to the alteration of your own history. When I look at our national and regional history, I see that has been altered too. That is how I got into my current practice.”

Meeting the artist again a year later – in less of a sultan look and more of a punk rock apparel – I could appreciate him bringing these reflections a step further. He told me that a big influence these days comes from his readings: “I take my time now to read, reread and unread the materials. I’m not certain if I can call this a method for my art, but at present this is how I understand my way of working.”

I saw your work at the Singapore Biennale 2016. Can you tell me how you responded to the Biennale’s theme ‘An Atlas of Mirrors’?

The way I read the theme is as a way to understanding mark-making, which echoes meanings and narratives of spaces. This is within the geographical context of the Biennale too. My personal response was conceived as an installation made of plaster and marble called ‘The Most Mild Mannered Men’. The installation consists of the busts of two individuals who were key in the demarcation of land in Singapore, Hussein Muazzam Shah and Thomas Stamford Raffles. The busts were placed one in front of the other, almost performing a dialogue, with some space between them. There are multiple layers of reading the work, despite the simplicity of the installation itself. To me, the bust, the plinths and the plaque with the names are markers of a dialogue. The nuances of this conversation were lost in its translation and recording. Complimentary – or in contrast – to the historiography of that narrative, the work was also to show the ambivalence of recording itself. It is a dialogue between stillness and interaction. The gap in between the two figures represents an interruption, which visitors traverses. That interruption is a metaphor for time, movements and progress.

What was the idea behind your performance ‘A hanging of 10 Paintings in an hour – Submitting to a habit’ at Objectifs, and how did the public respond?

The performance was thought out after a government agency declined the paintings to be hung over the windows of the exhibition space, due to its ‘historical significance’, and because it would disrupt the traffic flow at Waterloo St. It was also after discussions with the curators that the performance evolved. The performance was quite literally, a hanging of 5 of the 10 paintings. It did not take an hour, but just 30 minutes of course. The exhibition was discussing borders, and I was thinking how these exist within the structure of exhibition making too. I repeated the performance at the closing day, with a different format. There wasn’t any hanging this time; the performance involved me drawing over 40 photocopied papers of the first page of ‘Myth of the Lazy Native’ written by Malaysian academician and sociologist Syed Hussein Alatas. Though it was written 40 years ago, I find the text still relevant, and not only in the context of the show. The work discusses and reframes how a society is perceived.

Since the Moyang series, in your work we find continuous references to Malay figures of local history, and to the idea of Nusantara. Do you feel too that in Singapore there is a lot of emphasis in creating a shared past but with a strong element of artificiality? Why is this in your opinion?

One of the possible reasons is that the current narrative is all constructed. I can sound off very arrogantly and with a leftist view, but in school we were thought that there were these colonials that gave birth to Singapore; the modern side of it, that is. We have come to this period where we experienced so much economic progress that we realized we need to find rooting. In the literary world in Singapore, they consider the period before colonialism as amnesia, because it was constructed that Singapore didn’t exist before that. Historians proved that before Raffles, Singapore wasn’t a sleepy village, otherwise why would the British even bother coming all the way here? Singapore is a very small island and we have had so many neighbours that we were reliant on until today. Back then we had a whole connection with the Malay Kingdom, and these are the few aspects that we have failed to recognise because of our collective consciousness. There is too much alteration going on. That is why it is important to look further to find artists like Raden Saleh. I feel a connection with these individuals based on the history of Malays. We are all island nomads and in what was called the Nusantara region.

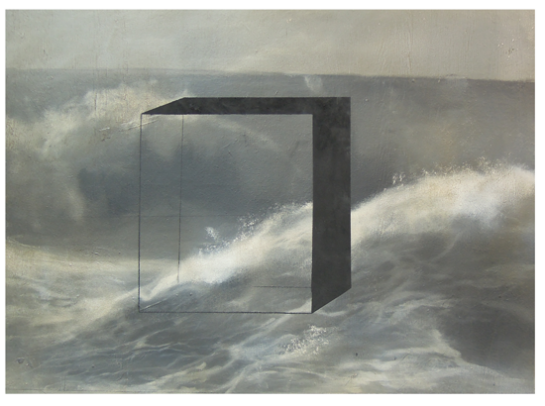

You have a series of paintings called “Homeland”, where you juxtapose geometrical figures to the landscape. How do you look at the concept of homeland in your work?

I feel the whole idea of homeland is turning into a myth itself. Because we are living in a very internet-centric world. The sense of belonging is not tied just to the physical space anymore, but also to the net space. That results in traditions depleting at a very fast speed and it is easy to lost your roots. I used to feel disconnected to my environment because I feel I don’t know anything about it. I know something, but I don’t understand enough to tell myself I know it. I look at archival images, and can I see how in this short time – 10 years is a bloody short time – it all disappeared. From having threes and a country filled with many forest areas, and we got so many tombstone-looking houses. The geometric shapes in my Homeland series paintings against landscape are a Kubrick 2001 Space Odyssey metaphor for human progress. It is a critique and also question: is this what we call evolution? If it is, why are we discarding nature? Mankind can go so far to destroy land, and ironically destroy to create an environment where we can feel safe and connected. You see the irony. In this respect, to understand history is not just an individual responsibility but one of the whole society.