THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 27

The work of Geraldine Kang

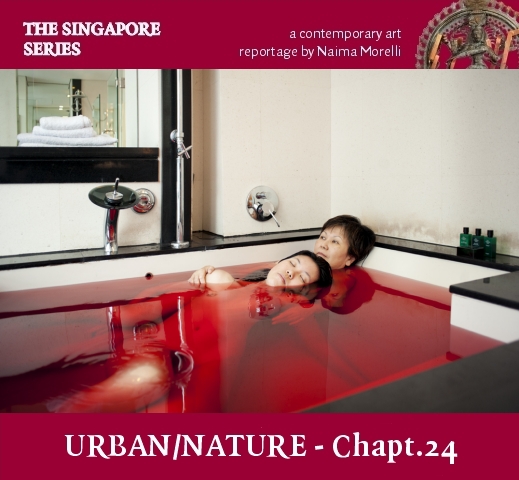

For Geraldine Kang, art-making has the functions of helping her process her thoughts and feelings and to get herself out of her head. In the awarded series ‘In the Raw’, she depicted her family members in surreal situations dealing with nudity, aging and death. The artist defines In the Raw as a “shock treatment” to introduce her parents to her art practice, which in the beginning they didn’t understand. In an iconic picture of her series, she is in bed with her parents, just like a little child would do, but with a photographic book showing breasts. The photographs encapsulate the lack of intimacy and the difficulty of maturing and dealing with desire where you share the same living space with your family.

When approaching sensitive themes, it is always good to look for models in other artists who tackled similar challenges. For In The Raw, the Geraldine was inspired by photographers Tierney Gearon and Sally Mann. “They use the naked body in a way that is quite natural. It’s not normal for people to bare their bodies in public, and nudity in proximity of the family is particularly uncomfortable. There are so many layers of meaning put upon the naked body. I was really fascinated by that and with In The Raw, I transplanted this idea into my own family.”

Nudity is a taboo both in Singapore and in Geraldine’s family, but that didn’t discourage the artist. “A lot of people ask me how I got my family to take off their clothes. And they are surprised when I told them it didn’t take that much. I just asked them: can you do this? They would be a bit uncomfortable, but they would do it anyway.” The artist now looks at In the Raw as an exercise of acceptance on both sides: “I see the work as a sort of compromise between me and my family. I show them what I am dealing with as an artist and see how far are they were willing to go with me.”

Mr. Kang, Geraldine’s father, said that when her daughter asked the family to take part in the series, he had no idea what she was doing. He only knew it was her school project. “I didn’t probe further as we did not want to add more stress to an already stressful situation. As parents, we try our best to help her in whatever way we can.” Mr Kang explains that being brought up in a conservative family, at first he was taken aback hearing about Geraldine’s project. “Took awhile to convince myself and my wife that it’s all about art and to just place our trust in her.” At the same time, they didn’t set any boundaries at all to Geraldine’s creative process. “I was fine as long as she didn’t make us a laughing stock through her pictures.”

In The Raw gained a lot of attention especially online. The series went viral when it was first published on (now defunct) poskod.sg. Subsequently it made it to a couple of small exhibitions locally (Etiquette at The Substation is one of them). This accomplishment, together with Geraldine’s stubborn commitment to her craft, showed her parents her seriousness about art. “Support really did change. They still don’t know what I’m doing, but they come to my shows. Sometimes they bring people to the exhibitions and they even help me with my work, my dad especially.”

When thinking about In the Raw, Mr. Kang notes that for him the series “is her way of bringing a message across through pictures. I kept telling myself this is art.”

Another interesting consequence of living with your family in a limited space, is also the lack of intimacy when it comes to romantic relationships. This paired to the lack of an outlet for transgression and the history and present of Singapore as a city port, gives rise to places like Geylang, KTV and love hotels, something that also provides inspiration for artists, for the evident coexistence of contrasting values. As we have seen, it seems that nudity in Singapore is taboo when it come to involve spontaneity, intimacy and affection, because it is directly linked with sex. It is drawing the boundaries between sensual and affectionate touch, which is problematic. In this sense having places for sex in a straightforward way is less problematic, as I learned by having lived around the karaoke-ridden Joo Chiat, mockingly dubbed “the dark side”, and the infamous Geylang.

Geylang is where the red light district of Singapore moved to after having been famously Bugis for decade. As the movie “Saint Jack” reminds us, in the ‘80s and before, Bugis was not all shopping centres and Bugis junction, where you can find cheap extravagant clothes and loud music. Another anomaly which has been examined by many artists are the KTV bars. These are supposed to be karaokes, but in reality are places where sexual exchanges happen. These spaces are so quintessentially Singaporean, to the point that artist Dawn Ng included a photo called “happy ending” in her series on Singapore.

I had the pleasure of entering one of these tacky, fancy places, during one State of Motion tours. These tours brought visitors to different locations on the city island, related to a movie. In each one of these locations an artist would have made work. The “Bugis Street” movie was actualised by having writer Amanda Lee Koe – author of Ministry of Moral Panic – who has us participate in a swank karaoke lounge event opposite Bugis Street, now an air-conditioned shopping mall. The work was called “No One Wants to Dance” and saw the writer dancing with Anita, a Bugis Street old-timer who tells us how Bugis Street “felt like home”. The video was a bit bewildering, as you couldn’t tell how much of it was complacency and how much of it was a conscious use of tropes and language to explore stereotypes and representation. Inviting the public to take part in this exaltation of kitsch was also a behavioural experiment which pushed them beyond the traditional boundaries of conduct, in that segregated, surreal space that are KTVs.

Working with nudes

The work of young artist Yanyun Chen is another interesting case in point. I showed it to my friends in Rome and they acknowledge something which is commonplace in all painting and live model classes at the Art Academy. Nude with charcoals, in different poses, with a strong emphasis on light. Nothing new under the sky. But in the case of Singapore, this is unusual. To travel to Florence to get the necessary skills for doing such work – Yanyun is a great traveller and takes any chance to expand her skills repertoire – is not something very common. Whereas the art academy in Rome right now is flooded with Asian students coming from all corners of China and Korea, mainly. Singapore never developed a love for realism and academic painting. That is why the work of Yanyun raises some issues. When trying to exhibit her work in different spaces in the Lion City, she had people coming up to her saying it would have been difficult, because she was drawing “naked people”. “The third time I heard it was just last week,” she told me with a bit of indignation. “We thought of ourselves as a progressive society, but we still haven’t quite gotten there in what relates to bodies.”

Yanyun was particularly bothered by having people in the art world criticising the body type and size of her models. She felt that her work revealed a kind of discomfort with dealing with bodies that is deeply entrenched in society. While this is not exclusive to Singapore, she was surprised that this kind of shallow criticism came from people in the art world, who are supposed to know best. After all, centuries of art from Rubens to Jenny Saville should have moved the art world to be beyond what is on the cover of a fashion magazine in terms of aesthetics: “There is an issue. I don’t expect everyone to like or understand every drawing, every work, but I’m really concerned that we brought these kinds of ideas, despite the fact that every kind of body has been painted or drawn. We still hold this kind of idea that one should paint the ideal body, make another Vitruvian Man or something.”

I point out another connected issue that is very much felt in Italy. From the art world to the “uninitiated” the naked female body is common place and doesn’t scandalise anyone, the naked male body still gathers uncomfortable laughs and criticism, especially if it is not represented as the Leni-Riefstahl-athletic-god archetype, but in a sensual way – as an object of desire.

In Singapore, a notable exception is the outstanding work of a prominent Singaporean artist who came into the scene in tho ‘80s, and whose practice focused on sexual identity and gender roles, often within the context of the traditional Chinese family. Speaking of beautiful nude drawings that are able to “épater la bourgeoisie”, we have the case of Jimmy Ong. His work is mainly charcoal drawings of people and pants, and here he explores the sexual, ethnic and national identity. The role these drawings have for him are, in his own words, a kind of “creative self therapy”, as the personal experience is often his point of departure. In recent years for example, he has investigated issues relating to marital roles, informed in part by his experience as a spouse in a gay marriage. However, we find a series such as Sitayana, exhibited at Tyler Rollins Fine Art in 2010 and subsequently acquired by the National Art Gallery of Singapore, which is a feminist re-imagining of the ancient Indian epic, the Ramayana, which is a founding mythology for all kinds of representations and mental models throughout Southeast Asia.

In art history, beyond Singapore, male homosexual artists have spent charcoals, and needle rollers on the subject of male nudity as male as an object of desire, women have generally not, staying on a self-absorbed representation of their own bodies. Always looking at themselves, never making the looking at themselves a non-issue by looking outside of themselves. I have observed first hand how this makes the male public generally uncomfortable, as for the first time they feel they have to live up to a standard. And many just don’t like it. There would be a lot to say about that, but let’s leave it at the fact that while we think we have already said it all in art about bodies, there is still a lot to explore, at least bringing different sensibilities beyond the mainstream to the surface. And the way people respond to bodies changes over time of course.

Singapore I feel still needs to pass the step where nudity is not seen as taboo, so of course gender and feminist-related issues are not a pressing concerns for artists. “Male of female doesn’t matter,” Yanyun Chen told me. “To me what’s interesting is that in art we are still looking for this kind of idealism.”