The Singapore Series – chapter 26

How space influences the art

The visitors of the Louvre museum are often upset when they see the Monalisa for the first time. Most of them, seeing it on catalogues, posters and mugs alike, they imagine it to be much bigger. Indeed, bigger than life. In a world where art and art history is experienced through the internet and catalogues, and perhaps less in real life, the size of an artwork is something that counts when it comes to the art market, but it is not really an indicator for art critics. And yet, if we take a sociological look on art, we come to realise that the size of a work tells us volumes about the conditions in which the artist works: it informs about the modes and the values of an entire art system. As mundane as it is, practical circumstances end up weighting on the final artwork more than we would like to think. Contemporary art is seldom made in poetic studios in warehouses, although in some countries that is the norm. In many other places it is done in subscales, a bedroom in your parent’s house or in tiny rented studio-apartments.

The way Singaporeans are experiencing the space definitely changes the way to make and experience the art, and becomes subject of the art itself. The problem of space for art production is more pressing than ever in a small, populated island like Singapore. As an individual, Singapore is not a country you move to and you can easily relocate, especially if you don’t either work for a company or study at a local school. Even if the city island doesn’t reach the business of Kowloon of the golden age, land and housing are still very precious currency. The island is small and rent is estimated to be one of the highest in the world. There is a not-so nice saying about Singaporeans going, that if you fart in the west you’d smell it in the east. Claustrophobia is very much a shared sentiment among Singaporeans, and those who can travel often. Claustrophobia pushes Singaporean artists to travel and come back home enriched with new stimuli

Space is not equally distributed; as crazy rich Asians can take advantage of huge pieces of land right in the middle of the island. For many others, the option is HDB, coming in a variety of forms and shapes. The housing problem of Singapore, as I came to know it, came in the form of respectable gallery directors living with a hosting a family who won’t even allow them to cook their own food — only light cooking, they say, which means merely boiling water. I have heard of a European gallery assistant who in one year moved house multiple times: “The first time I was sharing home with a girl who later I found out was a prostitute. The second time I was with a family who was locking me in. The third time I was hosted for a couple of months by the gallerist and now I’m living very far from where I work, Tampines. I have to take two busses and one metro to get there. People ask me why, and I say that it is the only cheap option available.”

In Singapore, the housing is administrated by the Singapore government trough the statutory board, which owns and manages the housing of 80% of Singaporeans. It is impossible to live and work without bumping multiple times into the government. The ubiquity of the government in business and society gives them a complete power over domestic power. Private and public life in Singapore are almost indistinguishable. Even if this is not immediately evident, the housing situation in Singapore is strictly correlated to the creation of a waged workforce in Singapore. In the ’70 and ’60 the kampong were wiped away along with villages and many shop houses. These cheap forms of housing were replaced by expensive rented flats who needed a sustained income to be kept. In other words, rents went up for a reason, to force people to work.

The wiping of the kampong life gave rise to a whole new set of problems, on the same page of the fastness of the Singaporean growth. One of the most notable is the way people would come together. Would the community of the kampong be able to come together after having their street destroyed? Geography and architecture do have a real impact on the life of people. There is a whole new lifestyle to be re-imagined. It’s like moving to another country without having really moved. The void decks we already mentioned are a demonstration of this forced way of making people come together.

Studio space

Some criticise the idea of artists needing to have a studio, saying that’s a western idea of what an artist should look like. One thing is for sure. The space conditions the thinking and the making. Artist Gerald Leow admitted that he was forced to destroy one of his works — a stone replica of a CD of The Slayers made in Bali by stone carvers — before he had the chance to exhibit it, because he had nowhere to store it. But he doesn’t complain about it, explaining that for him art is also a question of opportunity, and he put the same research and effort in small works as in the bigger ones.

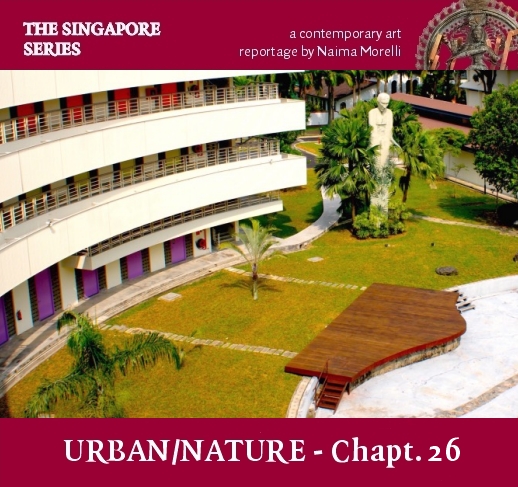

While older artists have their own studios, the majority of artists take advantage of the spaces assigned by the NAC (National Arts Council) built with Florida’s idea of artistic cluster in mind. On the NAC website you read: “If art is to flourish, it must have a place to call its own. [..] NAC’s goal is to provide artists and arts groups with accessible performing venues for their productions, and to create sustainable platforms where artists can collaborate with each other and interact with the wider public to bring the arts to the surrounding communities.” The NAC implemented the Arts Housing Scheme in 1985 to provide affordable spaces to arts groups and artists. Its main purpose is to give arts groups and artists a home within which they can develop their activities and thereby contribute to an active Singapore arts scene. Many properties in these arts belts are pre-war or old buildings such as disused warehouses and old shop houses, and to the government housing arts groups provides an important impetus for artistic creativity, helping rejuvenate these areas. The most important cluster for artists’ studios is Goodman Arts Centre, located in the Mountbatten district, and established in 2011 — previously the space which hosted LaSalle College of Arts.

Artist Donna Ong explained to me that it is not so straightforward to get a space there. You have to apply, compiling a huge form — which for Donna took over a month to prepare — and the government would come to make regular inspection to your work. Some see it as another way for government to control what artists are producing, but I don’t think that’s necessarily the case. As if it would be another enterprise, the government just wants to check the spaces will be used at their best and will deliver results. Again, what I see as the empasse here is not censorship per se, but more the problematic, yet enticing idea of wanting to forcefully managing the art production as it was a regular business.

Artists working from home

In most societies, the artist is seen as a rebel, not in the wider society, but also within its own family. Your typical artist would often seek independence and would fashion her own space according to her own creative necessities. The reality is of course not so utopian. In the beginning of my exploration of the young art world in Singapore, I was surprised to see that the majority of young artists still live at home with their families. Their living space is often their working space. This happens in the case of emerging artists who don’t make enough to sell their work, but also in the case of artists who are enjoying financial success. Independence at all cost is not the case here. While in Italy, the artist would just wait to save a little bit to jump on their independence, Singaporeans deem it best to be waiting, also because rent is crazy high.

The expression “moving back with your parents” is a sign of scaling back, even of crisis for many artists in societies which tend to have kids leaving the nest at seventeen or so, like in the US, Northern Europe, Australia. However, in Singapore, family is something important, strong and present. Being Italian, I see similarities with my own country. However, in Italy many artists I have interviewed didn’t really want to invite a journalist to meet their parents, and possibly hear embarrassing stories from the artist’s adolescence (which is of course what I’m all about).

The first time I visited artist Ruben Pang, he was making work in his small room at his parent’s house in Sembawang, and making the bigger works in a small studio which he described as pretty tiny, “probably the size of the kitchen”. Most of his works are stacked at the entrance, while others were in his room. The influence of his parents on Ruben’s career is clear, being that his father is very invested his son’s career. Ruben’s father works in jewellery and is an artist as well, and the other siblings also study art. This is not a common occurrence, but of course it helps to create a connection — or even tension in some other cases — when you live under the same roof.

This sense of family pervades many sectors of Singaporean society. The government for example is perceived as a stern father, and the society is defined as paternalistic. Order is reached through strict control. While family values are spread all over Southeast Asia, Lee Kuan Yew appealed himself to the traditional Chinese and Confucian mentality, where order comes before individual freedom. This is such a widespread sensation among artists, that when they get grants, it feels like their parents paid the ticket to go abroad. As artist Eugene Soh told me: “It is the government that is paying to send us overseas, but it’s like being constantly supported by your parents.”