THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 25

HDB

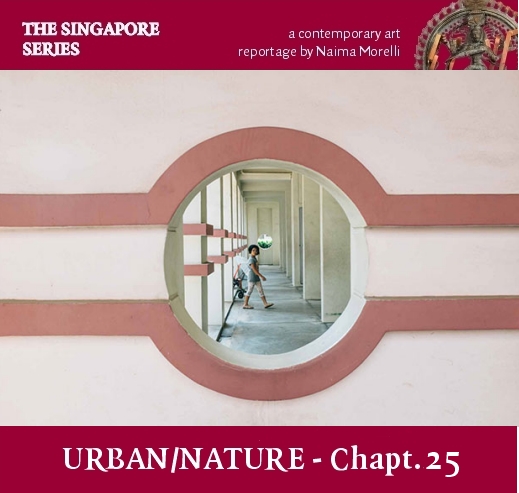

“Yearning is the dominant theme that runs through all of my work,” said the outstanding photographer Nguan to The Straits Times. “Singaporeans are restless by nature – we have wandering hearts. This picture describes the longing to be in a different place or time.” Nguan is probably the artist who best caught the poetic, ineffable, paster colour heat of Singapore. In his delicate photographs, depicting mundane moments, suspended in silence, he is able to capture the soft alienation of his own city.

In 2016, he took over New Yorker Photo’s Instagram for a week, posting pictures of Singapore every day and making the eerie aspect of the little red dot known to a public who recognised Singapore mainly for its economic achievements. In his most famous series “How Loneliness Goes” he featured 23 photographs that riff on themes of solitude – a cracked plant barely held together, a woman eating alone in a coffee shop and, of course, people waiting at void decks. A favourite subject for the artist is the HDB buildings, which really present themselves from the outside of those rosy, soft hues Nguan so lavishly bashes himself in.

We have mentioned how the kampongs, which are defined by the government organs as “unhygienic squatter settlements”, have been wiped up to leave room to the HDB buildings. Early HDB flats were designed to be simple and utilitarian to optimise space usage and keep costs low. The ease of construction was another important factor as homes had to be completed quickly to house those who were displaced. Then with the growing awareness of a pleasant environment, the surrounding spaces around estates was improved over the years, from providing greenery to have minimal recreational spaces or facilities.

The construction of new generation HDBs is not stopping. Only in 2016, more than 1 million flats have been completed in 23 towns and 3 estates across the island. Today, HDB flats are home to over 80% of Singapore’s resident population. The experience of the different generations of building can be quite diverse. I remember one afternoon walking through an old estate of low-rise buildings of a few floors in Mountbatten, ready to be torn down in a few months. The human size of the buildings, the surreally green lawn, the presence of a river (later I discovered it was kind of a haunted one, because many people throw themselves in the canal) and the silence gave me a quieting feeling of being almost in a world from a children’s cartoon. There were indeed kids playing soccer in a void deck, and Malay music was coming from a window. The doors were certainly not pristine, the whole structure of the building looked a bit like brick and mortar, all the lines were not straight and the paint was scratched. It was all very human in a way and it gave me a sense of peace.

However, I also remember being driven through jungles of high-rise, gigantic HDB complexes in the eastern part of the island, with huge buildings that looked all the same, all perfectly industrially built. That made my heart sink. It was scary. It looked completely inhuman. I remember the driver praising the modernity and facilities of this kind of building, and the fact that they were sought after. Certainly he would have looked down at the poor-looking Mountbatten buildings. And yet, it was 30 minutes we were in the car and the succession of sleek, threatening HDBs seemed to never stop. However, it is where we most feel deprived to what we consider to be human, that we manifest the essence of it.

When space tries to deny our identity, humans never give up the continuous doing, undoing, customisation and familiarity of even the most hapless of things. In that dynamic, we can see how the tension between bureaucracy and imagination plays out into the living environment. This is exactly what the artistic duo Eitaro Ogawa and Tamae Iwasaki and architect Tomohisa Miyauchi set out to document in the series “HDB: Homes of Singapore”.

Over three years, they documented how apparently similar HDB flats can be modified to reflect character, lifestyles and cultures. The inspiration behind the book came about seven to eight years ago when Iwasaki and Ogawa – permanent residents originally from Japan – were considering buying a HDB flat. “We didn’t really have a good impression of HDB flats. They looked very rigid and similar to each other, and we were not very sure about living in one of them,” Iwasaki told the Web magazine TODAY.

“Throughout this project, what touched us the most was the kindness of people’s hearts, the lives they live and the generosity that enabled such rich story-sharing. Singaporeans often speak of the lack of culture in Singapore, yet we found this to be quite the contradiction because we discovered much culture residing in the topic of the HDB flat alone! Culture was evident in each home. Culture was lived. At the end of the project, we gathered plenty of photos. But more importantly, we got to know Singapore a lot more through uncovering the multifarious and personal way of living beyond the exteriors of the HDB flat— and this was something we wanted the photographs to capture.”

I first encountered the photographic series within the Singapore Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Located in the Arsenale, the Singapore pavilion tackled the numerous issues Singapore is facing, presenting some solutions that have already been implemented and others just planned.

Right from its title “Space to Imagine, Room for Everyone”, the Lion City sees imagination as the solution to the notorious housing problem on the island. Imagination, however, is not a given in a city that has achieved incredible results in fields such as economics, yet paid a high cost in terms of spontaneity and personal initiative. Now the nation is taking a step back, trying to look at what has been lost in the stream of modernisation. The pavilion looks at the main protagonists of this process of resurgence, namely the state, the community and the individual. Through the projects presented, we see how the paternalistic state is slowly loosening its over control. Citizens are gradually feeling freer to create their own gardens, build their own communities and start unleashing creativity. A series of glass boxes show the interior of everyday Singaporean houses, which consisted in part of the aforementioned series “HDB: Homes of Singapore”. The series wanted to lend a human element to a state which aspires to be considered by the world for more than its GDP.

The Void Decks

In Italy, we have this beautiful thing call a “piazza”, the square, which still holds a role in social life, even at the times of the internet. In northern towns like Treviso, mayors want to “requalify” old squares which have great potential to became places of aggregation, because they perhaps have some nice monuments. However, if people hang next to the river, it is not only because it’s a nice view. It’s because there is the tabacchi store next to the river. Because there are some benches, and also because it’s on the way between the restaurant where young people go and the next bar. And there is causality too, and a whole lot of irrational elements that move people, which are likely to never being taken into consideration on the drawing board. One corner can become old people’s favourite corner, not because it is special in any way, but because it has been elected that for no rational reason.

The Void Decks in Singapore are an emblem of that. In building the public housing, the Singapore government put a lot of effort into creating cohesive communities within the different neighbourhoods, and created community spaces meant to be interactive. During my first research trip to Singapore, I lived for a month in public housing in Geylang Serai, and found the division of spaces and general structure well designed. And yet, I seldom saw people hanging in those void decks designed to be shared spaces for people to gather. It wasn’t nearly as lively as the “commercial” area of Geylang, where the market was.

Because of their eerie quality, many artists looked at these spaces with interest – often through video, which relate this non-place to the idea of time. In 2008, the artistic duo Perception3 created the video “Terminus”.

The video shows a perspective of immaculate void decks shaped by the passing of light, which was accelerated in the video. It is a space that remains empty, pure and solitary throughout the passing of time.

To the artists, this public space unique to Singapore and its ubiquitous presence under each public housing block, serves as a poetic reminder of the disconnect and dualities that exist in our modern cityscape: “It is a space where neighbours meet, and avoid one another. A place to breathe, but not to linger. A blank slate for the imagination, and a view into the emptiness that surrounds us.”

Sarah Choo, whose work has always been concerned with social alienation and isolation, made an HDB void decks subject of the “Waiting for The Elevator” video projection. Unravelling on a long screen, the video incorporated documentary footage taken in various public housing estates around Singapore. The work was commissioned to the artist by the Esplanade, an exhibiting space located in a tunnel. The artist adopted the long format to make use of that tunnel and convey people’s experience. Like in a dream, you seamlessly transition from a void deck to another. The effect of this composited panorama and of fragments over time really gives back you a feeling of sadness, solitude, longing and wait, that is embodied by the void decks.

“I wanted to show the Singaporeans something that is always there, but they don’t realise and they don’t stop look at, which is the void decks,” the artist told me. “And it’s so funny, because it’s a space which is designed for social interactions amongst the different races in the building, but that’s not happening. I don’t see that happening. So I want to present that scene to them and help them reflect upon why this is the situation with the void decks.”

In truth, these spaces exemplify the problem of segregating people’s home in residential areas and bringing the commercial activities in malls. In separated areas, interaction won’t spontaneously happen as it would be in a mixed area. In Singapore’s HDBs, the problem is no so much the houses per se, which can be very comfortable and provide higher living standards for citizens – as it is its original purpose. It is that the reconfiguration from kampong to a flat, made people more comfortable but more distant to each other.

In this picture we know that technology was the final straw. The participation happens on the internet, and that is a very good thing when it comes to paying a bill, so you don’t necessarily waste half of your morning at the post office. As we know and have seen, it is also making people globally closer, but individually more distant.