THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 8

Economic Agenda for the Arts

In the beginning, when people were talking to me about art in Singapore, I was hearing two parallel stories. In one of these two stories, the art was born from individuals who dared to go against the grain, challenge the status quo, coming together to build a community. The other story was that the government decided they needed art, and so they made it happen. I slowly realised that it wasn’t merely a different point of view. Contemporary art in Singapore was twice born.

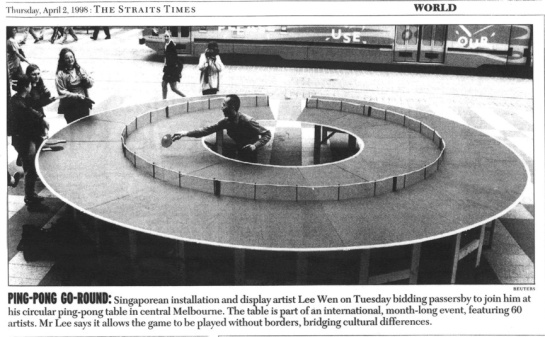

The first time it was a natural birth. Grassroots. Tang Da Wu, Lee Wen, Amanda Heng, Vincent Leow, Suzanne Victor were among them. Names inextricably associated with the early days of The Artist Village. The second was more of cesarean section. My midwife housemates explained to me how differently these two worked. In the natural birth, it’s all up to the mother. There is a lot of suffering involved, but that suffering is good, because the mother instinctively knows where to push, which position to take to get the baby out. It’s her bodily knowing, no one else can tell her how to do it. It’s the most natural thing in the world, although it might be dangerous. Back in the day, giving birth could often result in the death of the mother or the baby, or both. But when it was done – my midwife housemates assured me – it was about the most beautiful feeling in the world. The mother could finally take in her arms that ugly purplish sticky thing which is a newborn baby and feel completely happy, serene, fulfilled and relieved on the most existential level. Well, that was The Artist Village. Little money from the government, all going forward with a day job and a lot of opposition from family and society. The first attempts might have looked ugly like a newborn baby, but the love was definitely there, and the satisfaction for creation too. They must have felt that they were really up to something. In hearing about people telling about those pioneer times, you’d feel the quiet heroism.

When it comes to childbirth, a cesarean delivery is a completely different business from natural birth. In my mind, the cesarean was nice and neat. However, my housemates warned me not to be fooled by appearances. It was a surgery in its own right. She explained that the woman stands on a cold, metal bed, partially anesthetized. You couldn’t put the woman to sleep because if she has breathing complications, she needed to be able to react. So half of the body was completely asleep, while the other half is vigilant. This particular kind of anesthetic used allows the woman not to feel pain, but to feel touch. The operation starts with a small hole right before the pubis. It’s a very small hole the size of a button. I looked at the buttons of my pullover and I cringed. “Was it a vertical cut on the stomach, and then they would extract the baby from there?”, I asked. “No, not at all”, the housemates said in unison. “That was for goats. Goats are opened part to part. So back in the day, they would make a long longitudinal cut just below the belly, and then extract the baby from them. Today they find that it is better to make a small incision – the size of button as we were saying before you interrupted – and then slowly but surely, they’d open it with their hands.” They mimicked with synchronized movements of the opening of the button-size hole. They looked like Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Just as cheerfully evil.

“The worst part is”, said Tweedledum in a voice engrossed by the gory details, “Is that because of the epidural anaesthesia, you don’t feel pain, but you feel the hands coming into your guts and scavenging.” “And scavenging and scavenging”, echoed Tweedledee, “until you get the baby out.” Then the smile transformed in a grimace of sadness and she abandoned herself on the kitchen chair. She said she was born like that, and that made her very sad. In natural birth, the baby actively collaborates to get out, pushing and struggling to come to life. With the caesarean, the baby is completely unconscious. They were just robbed from the womb in their sleep. They didn’t transition from one dimension to the other. What had been their whole universe so far, the mother’s womb, was suddenly shattered starting from a small button-size hole and then some hands from the ceiling would come and toss the baby this cruel, cruel world in the most punishing way. The Iron Maiden couldn’t have made it more apocalyptic. No one asked the poor baby, nor did the baby have any involvement in it. They were born passive. “It’s good that we don’t have memories from when we were so young”, said Tweedledee, “because that sounds like a real trauma. And it’s not finished there”, echoed Tweedledum, just when I was about to sight for relief. “When the woman gets home, she feels a whole lotta pain, because of the cut. So she has to take care of the baby and endure the pain of a surgery.” So a decision which might have been taken to avoid the pain of a natural birth, results in even more pain after. That’s the irony of it.

So can you see some similarities with the Singapore art scene there? The cesarean is exactly how contemporary art in Singapore is born again in the new millennium. It has the government as a good surgeon, and a couple of midwives assisting in silence, opening the hole with their hands more and more and more, until you start seeing the baby, and then take them out of their sleep.

While in the ’90s, the art scene was born from the ground up, in the new millennium it was built from a top down approach. What happened is that in 2000, the Singaporean government decided to establish themselves as a global city for the arts. It was an operation of re branding in its own right. Before that period, they didn’t really give a damn about art. Art was seen as useless. Of course, when midwives tell you what their job is about, art does sound like nothing in comparison. Daily, my housemates were assisting the creation of a human being – the mystery of life. And what are you doing instead, dear Duchamp? You are putting a urinal upside down, which actually some saw as a metaphor for a uterus, so the connection with birth is there, however most of us will still see just a urinal upside down. Then, when you compare the life of an artist, thinking and thinking, all to make one single brushstroke and be considered done for the day, it really looks like nonsense from the outside. Do you know how many things you could have been doing in the meantime? Economic empires were conceived while you were looking at that damn white canvas. In fact, that’s what Lee Kwan Yew did. Quoting the title of his memoir, he factually brought Singapore from third to first world country in one generation’s span. He didn’t do that by making art a priority. There are nations that, although very poor, have art and culture in their DNA, and these grow side by side with prime necessities. Then there are others who decided to take care of the practical, urgent needs first, and then think about culture later. Seeing how far Singapore has come in just 50 years, we honestly can’t criticise Singapore’s choice of attitude. So in the ’80s, the president was busy developing Singapore as an international headquarter base for transnational corporations in manufacture and services. In the ’90s, when the guys at Artist Village were doing their act, the government took care to develop Singapore as an e-commerce hub for hi-tech companies, an educational centre for international institutes, a regional medical centre and a tourism capital. Moving up on the pyramid of the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it became clear that art and culture were needed for the development of economy, so art was finally seen as something useful. From the 2000s onwards, the government concentrated its efforts on developing Singapore as a global centre for the arts, culture and entertainment.

Art as economic force

So how did the Singaporean government come to realise the usefulness of the arts? Was the old generation of artists responsible for that, or the presence of spaces life the aforementioned Substation, which positively pressured the government into making policies and made the whole art scene gain more and more momentum. Or perhaps the new predisposition was simply the observation that all over the region, the contemporary culture sector started to look like a powerful economic force. People were travelling to Jogjakarta not just to see Borobudur, but also to visit the ateliers of contemporary artists and perhaps make some purchase. Besides, Singapore doesn’t have a Borobudur equivalent, so if there was one sector that needed to be enhanced, that was precisely the contemporary. While in terms of heritage, the small nation state couldn’t compare to Indonesia, they had something else over Jakarta. Notoriously, the Indonesian government don’t care about contemporary art, and the rest on the laurels of traditional culture. On the other hand, Singapore had an observant government willing to observe, plan and act.

So, now that the arts and culture sector start looking like a key economic deliverable, even that reversed urinal tagged “R.Mutt” started making sense. Now the problem was, where do you look for culture in a country that just forgets about it and has head-down into work, work, work for the last 50 years? The faceless bureaucrats must have looked at each other until someone came up with an idea: “We make it!” After which silence probably followed. You couldn’t read that in the faces of the faceless bureaucrats, condemned to a lack of expressiveness by their own definition. “We commission artists to make it up!”, the same faceless guy proposed. And finally the claps. Emboldened by the clapping, the bureaucrat heightens the stakes: “And we will look at our past! We will look at the past of the whole region!” Triumphant music. The curtains closed. The public was ecstatic. The first act was finished. You could finally go to the toilet. Why are you still standing there? Go! Go!

You look at yourself in the mirror of the toilet, with that red lipstick on your mouth slightly smudged and you have an epiphany. It is now crystal clear to you. History is a made up narrative. Art history in particular. Written by the winners, taken at face value from school kids. You saw it in Indonesia, where a few years ago school kids were learning that communists plagued the archipelago and deserved to be killed. You heard it in Australia, where in the seventies you still had text books stating that Aboriginal blood should have been washed down. And of course, Italy, where in the north they convinced people that they are better in comparison to those in the south because in the north, they are descendant of a fantasy-land state called Padania – which wasn’t any more true than King’s Landing. Like the latter, they even made a movie about it and for some, that was enough to legitimize it. In the dirty mirror, you ask yourself, “Where do you learn about the truth?” Is it in school? From the TV? Or on the internet? Perhaps in the magazines. As long as there are charlatans like myself writing for magazines, you shouldn’t believe them. Let’s take a sociological approach to the matter then. For Castoriadis, the imaginary in a society is the central imaginary significations of a society. These are the laces which tie a society together, the forms which define what, for a given society, is real. In my time in Singapore, I gradually realized that young artists in Singapore couldn’t really be like artists in other parts of the world for one simple reason. They were not just doing their thing. They were thinking of just doing their thing, but what they were really doing was shaping the national imaginary. And commissioned to do so.

Just a few years ago, in 2000, in Europe we weren’t hearing much about Singapore yet. So what I knew came from the mainstream narrative constituted by Strait Times articles and government plans. We already mentioned the two objectives of the aforementioned Renaissance Plan, namely establishing Singapore as global art city, conducive to creative knowledge-based industries and talent. The second was to strengthen the national identity and sense of belonging among Singaporeans by nurturing an appreciation of a shared heritage. In putting that theory into action, they declared themselves aware in striking a balance between the, humanistic and of art. In order to be attractive, Singapore not only had to be only a global city, but had also to maintain a local flavour. On a practical level, the action plan translated into taking local peculiarities and globalizing them. Another part of the scheme was to import talents and export home-grown skills, as we mentioned in the previous chapter. In this scenario, the job for the artists consisted of creating an imaginary for Singapore.

Another definition of imaginary is the creative and symbolic dimension of the social world, the dimension through which human beings create their ways of living together and their ways of representing their collective life. This imaginary is not simply fictional or unreal, but it can have very real consequences. The practical Singapore is a living example of how imagination – and the subsequent categories of thoughts which are generated from it – can actually shape the way of living in an entire nation.