The Singapore Series – Chapter 1

Writing history

When we were studying history in school as kids, we perceived it to be a fixed, unchangeable entity. “Only history will tell”, is still a common saying, which identifies history as the ultimate judge, operating with the fairest of methods. We see that mentality in art history as well. Van Gogh is your typical case in point of the neglected artist in his lifetime who History then recognised as one of the major artists of the 20th century. At the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome my professors used to see art history as a force opposed to the art market. Market success was described to us students as kind of a cheat. Conversely, history couldn’t care less about money and other such vileness. Apparently what history remembers are the true masterpieces of real artists, not certainly what’s up on the stock market. Good art is what will stand the test of time.

While I subscribe this view, I’m also aware that along the winds shaping the rocks of history, market forces are in the picture as well. Today more than ever. History is a re-reading of the past according to what the present values important and useful. The retelling of every story necessarily implies highlighting some elements and hiding others. It does that in a functional way. In this sense, we can consider the old saying, “History is written by the winners” has been true until the ‘80s came along and postmodernism challenged this notion.

With postmodernism, those the Americans called “losers” (and Ancient Greeks called “tragic heroes”) had their say in history for the first time. A main feature of this current of thought was indeed the concept of destroying the Grand Narratives, the big history of battles and defeats, kings and queens, big systems, giving equal weight, value and dignity to the minor stories of peasants and slaves. You might think Singapore, for the longest time subjected to the British, embraced that ethos. Indeed when walking into the National Museum, in the section dedicated to local history you will read about the military schemes of the Japanese and their strategy, see two wedding rings and watch the animated video-story of two ordinary Singaporeans who got married during the occupation. Grand narrative and minor narrative side to side, it seems, are contributing to build a new, official narrative for the city-state. This official narrative of Singapore changed over time and keeps on changing according to the needs of the moment. As we see all the time in all the major religions, the point of the sacred texts is not really to explain, but rather to legitimise the norms of a religious society. As we will see, many artists in Singapore have accepted being put in charge of this task by taking the government’s funding to realise their projects. The definition itself of contemporary art is that it can’t convey a single meaning. This makes it particularly apt to express the different ethnicities and religious instances of a multifaceted and diverse society and especially difficult to be channelled into straightforward propaganda. Artists are of course well aware of what is expected from them, but instead of delivering on it hic et nunc, this dynamic often becomes part of their work. The system becomes the content.

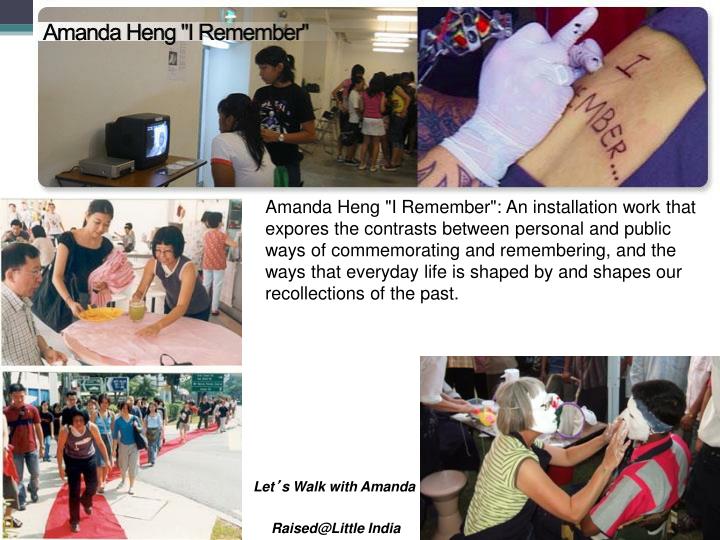

An example of collective re-elaboration by artist is to find around the haunting period of the Japanese occupation of Singapore. However brief this is a tragic period for Singaporeans. On one hand, the Japanese facilitated independence. On the other, they perpetrated horrible abuses on the local population. This period was explored by a number of artists during The Necessary Stage’s M1 Singapore Fringe Festival 2005, themed ‘Art and War’. Among them, the braided performance artist Amanda Heng, a pioneer of performance art in Singapore, brought a performance called: ‘I Remember… (Singapore)’. The time period explored was precisely when the Japanese occupied Malaysia and Singapore in WWII, from the early 1940s until Japan’s surrender in 1945. The way the artist tackled the theme is through memories: personal memories versus the collective. In the performance, the artist got her back tattooed with the words “I Remember”, to remark the indelible quality of memories and the fact that we carry them on our bodies and minds for the rest of our lives. She also presented video-interviews with Singaporeans who lived tough this period. The rawness of the personal recalling constituted a stark contrast with the sanitised and mediated stories of war, as they are presented in public commemoration, like in the National Museum of Singapore. Memories – Amanda Heng seemed to suggest – are the bricks with which individuals and society build their present.

The founders

Since every story starts with a “Once Upon a Time”, the first case in point in a book about contemporary art in Singapore, must be the foundation of the city state. Where did it all begin? What was there before? Who must be considered the real father of the nation?

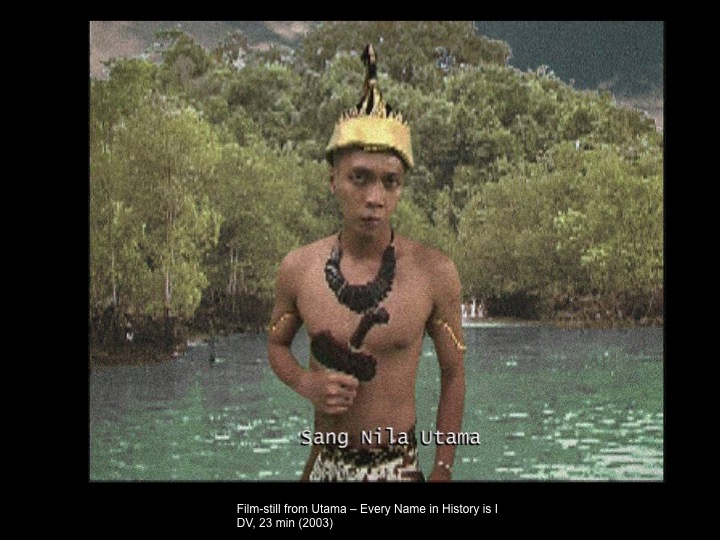

A beautiful artwork which ponders these questions and encapsulates the coexistence of multiple narratives in contemporary Singapore is a video called “Utama: Every Name in History is I” by Ho Tzu Nyen. I first encountered the work in the contemporary section of the National Gallery of Singapore. Moving the curtain hiding a dark room, I was immediately mesmerised by the twenty-minute video which had the ‘VHS-straight-out-of-the-‘90s’ look. It was telling the story of a nation with the Homeric tones of an horal history. The images looked like they were springing right from the viewer’s imagination. The acting was highly theatrical and the postures of the characters were dramatic. The protagonist was Malay prince Sang Nila Utama (in the video impersonated by another Singaporean artist, Zulfiki Yusoff), who is believed to have founded Singapore sometime between the 13th and 14th century. In the video, we see the prince going on an expedition to look for the ideal site to found a city. Together on a small boat with his assistant, he finally sees a white and beautiful stretch of land called Temasik and tries to reach it, but his ship gets struck by a storm and begins to sink. Everything was thrown overboard in an attempt to lighten the boat, including Utama’s crown. When they landed on the island, they went hunting on an open ground and saw what came to be identified by Utama as a lion (curiously lions are not native animals to Singapore). As the legend goes, the ruler decided to name the island settlement Singapura, meaning “Lion City” (singa meaning “lion” and pura meaning “city”, in Sanskrit). In the video, the story of Utama alternates with other voyages by boat of other explorers, from Englishman Sir Stamford Raffles to Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Captain James Cook, Alexander the Great and even Julius Caesar.

We know fluidity and coexistence of multiple versions of a story is an inherent characteristic of the myth. As Plutarch wrote about Greek myths: “These histories have never been, but they are forever”. In the oral transmission, it doesn’t really matter which story is true and which is false – they are all true at the same time. Holding multiple, contrasting truths in mind is a sign of a plastic mind.

In this framework, Ho Tzu Nien’s “Utama: Every Name in History is I” explores Utama’s genealogy as the descendent of the Malay-Hindu prince Iskandar Shah as well as a distant relative of the Chinese eunuch-admiral Zheng He. In the artist’s words, the film is “an attempt to summon forth the spectre of Utama. Ultimately this is a film about the intertwining of myth and history, the impossibility of ontology, the instability of all beginnings.” At the end of the movie, we see a typical theatrical device, where the protagonists step “offstage” and into present-day Singapore, where we see both the statue of Sir Stamford Raffles and the statue of the Merlion. This figure with a lion’s head and a fish’s tailfin is today considered a national symbol, but despite its mythological appearance, it was actually conjured up by the Singapore’s Tourism offices in the ‘70s. The archetype gives way to the marketing strategy.

First presented at The Substation in 2003, the work was intended to encourage Singaporeans to think about the origins of their identity. Ho Tzu Nyen declared to have realised “Utama: Every Name in History is I” as a counterpoint to the cult of Raffles in Singapore. In contemporary Singapore, the mythical Malay founder never shared honours with the British administrator. On the contrary, the figure of Utama and his name and mythological story has been gradually erased from public consciousness.

So what we read today in the official accounts of Singapore’s history is that the nation-state was founded in 1819 by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, as part of the British colonial empire. Back then, Singapore wasn’t the most crowded of places, accounting only for 1000 inhabitants, but it definitely was not the empty pond or “sleepy fisherman village” it came to be described as later. It was already a lively trading post and Malay fishing communities were living in the area – and apparently pirates too. Singapore was the second island of the region to be occupied by the East India Company (EIC), following the acquisition of Penang. Stamford Raffles was appointed head of a civil government to run Java and Sumatra. The colony was added to the EIC Indian empire, reporting directly to Calcutta. In 1818, three years after the Napoleonic war ended, Java was returned to the Dutch and its governor Raffles was assigned to Singapore. Raffles had an expansionist mentality, and he persuaded the Sultan of Johor to cede Singapore to Britain, which officially acquired it in 1819. On an administrative level, the East India Company decided to consider Penang, Melaka and Singapore a unicum, making the latter the administrative centre.

Before Raffles became central to Singapore’s narrative, the first two figures presented as myth-makers, and embarked on the effort to build a coherent narrative for the city-state, were actually of Indian ethnicity; Singapore’s first minister for culture S. Rajaratnam and Singapore’s third president D.V. Devan Nair. Their vision lasted from the ‘50s to the early ‘70s and, according to Michael D. Barr: “The national culture and identity swirled around images of a Singaporean melting pot of races and cultures, all pulling together and defying the odds for a better future.”

The two ministers clearly pushed aside the figure of Raffles, in order to get rid of the colonial past and start anew. In the beginning, Lee Kuan Yew held the same line, until the ‘80s. While the figure of Raffles was rehabilitated, Lee Kuan Yew came to be seen as a new Raffles in a way – the true father of Singapore, obscuring all others. A third father of Singapore of sorts.

One young artist whose art practice revolves around reconstructing the Malay’s narrative of Singapore is Fyerool Darma. Fyerool is a young artist living in the area of Singapore called Tampines, where the HDB (the public housing) have soft pastel pantone colours. Looking for the right block, I passed through a void deck who had some scattered remnants of a party that had probably been thrown the previous night. Fyerool welcomed me at the door. He had very gentle manners, round glasses and a round face. He was wearing a white shirt, jeans and had a blue cape thrown on the casual look, which made him look like a young hipster sultan.

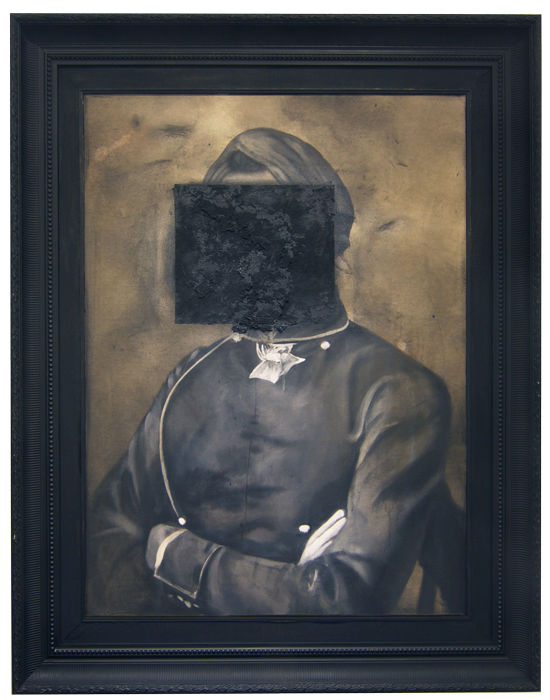

The living room had all the furniture covered by a layer of plastic, reminding me of a trope of the Italian house from the ‘80s in the movies of Italian comic Fantozzi. The difference was a big Islamic art calligraphy piece in gold on the wall, something definitely not Fantozzi. Laying against the wall was a portrait without face. That too was wrapped in plastic, but you could still see part of it. The figure depicted had his arms crossed, and wore a uniform and a turban. On the face there was a squared burned black rectangle and the texture reminded me a little of Alberto Burri’s charcoaled canvas. The work, acrylic and charcoal on canvas with charcoal on wood, was called ‘Portrait No. 1 (Raden Saleh)’ and was part of Moyang series. Just next to this work sat another one. The title was ‘Portrait No. 4 (The progenitor, pendatang or probably Seri Tri Buana)’ and was a canvas cut in half with all the framing. You could see only the lower part of the body of the character, which looked as if it were painted from an old photograph. He was wearing a sarong and hold a book in his hands.

Moyang is the Javanese term for ancestors. In the series, the artists looked at his spiritual fathers in the Malay pre-colonial history of Singapore. These include figures like Raden Saleh, Ali Wallace, the assistant of the author of “Malay Archipelago” Russel Wallace, who was heavily involved in the collection of butterflies and specimen within this archipelago. “In this series I reflect about the role of the tukang. This term means the working man, specialist, crafters,” explained Fyerool. His day job was being an art preparator at the art gallery Sundaram Tangore. Watching artists making the work and bringing it to the gallery, they pushed him to look at the minor narratives which, although invisible, are constitutive of an artwork. “It makes you aware of the hierarchies in art,” he continued. “The ideal of the artist is someone doing everything by himself, but if you think about Leonardo Da Vinci in the Renaissance, he had different tukangs, many art assistants. Andy Wharol had his tukang too, and all of them were not credited.” Another figure that appears in the series was Sang Nila Utama himself. With this series of work, visually based on photographs and conceptually based on historical accounts from the pre-colonial to the colonial era, the artist wants to give recognition to the forgotten Malay history of Singapore and tied it to the idea of Nusantara.

In Moyang, Fyerool kept himself close to figurative painting, but with a conceptual slant to it. The series was exhibited at Flaneur Gallery and had the support of the artist council, which made me think that after all the government wasn’t so against a Malay narrative of Singapore. So here it was in front of me, an artist from the youngest generation of Singaporean artists, the generation which was so often accused of caring only about the market, trying to bridge the disconnect between the present, memory-deprived Singapore and the wider history of the region. The question for him was how to manifest the many possible narratives that have shaped the island’s past and will continue to shape the island’s future.