THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 22

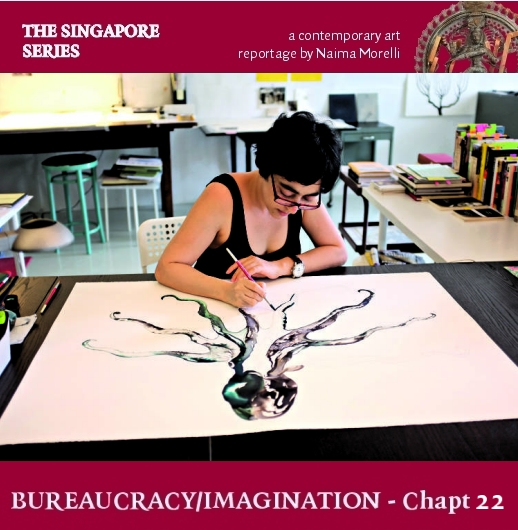

Shubigi Rao

When it comes to the power of imagination, Shubigi Rao is an artist that masters it. Shubigi has the capacity of completely drawing you into her world and work, which is complex, multidisciplinary and deeply entrenching. However, she also touched upon the other polarity of this chapter: the bureaucratic aspect of life. Indeed, in her critically-acclaimed 2016 book called “Pulp: A Short Biography Of The Banished Book, Vol I” , she addressed censorship, book destruction and other forms of repression, as well as looking at books as a symbols of resistance. The project is being developed over 10 years, in which time the artist is investigating the destruction of books and libraries around the world, collecting video testimonials from people involved in saving or destroying books, such as firefighters who tried to save the burning national library of Sarajevo during the civil unrest in the 1990s, or others who smuggled books and paintings to safety during times of cultural unrest.

At the end of 2015, Shubigi was sharing her studio with Donna Ong at the Goodman Arts Centre, and while Donna’s side was a jungle of plants and exotic object, her side of the studio was filled with books, notes and paper. I remember that during our interview she told me about the sadness of seeing her family’s library burned to the ground. When in a heartfelt description of what happened, she told me how she missed it, she almost brought tears to my eyes. For the first time as an interviewer, I had to look away and interrupt the eye contact. However, touching a number of subjects tied together by Shubigi’s outstanding art practice, I walked away from the Goodman Arts Centre feeling energised, like after flying in with an assisted hand glider on culture, human knowledge and everything that is of meaning in our world.

“My life growing up was really lovely. My family used to live in the Himalayas”, she told me. “I didn’t have a lot of friends of my age, but I had a lot of books.” Shubigi first came to Singapore in 2002 from India. She had wished to study art in New Delhi, but in the ‘90s she found the scene to be incredibly patriarchal. In line with her and her family’s long-time fascination with language and literature, she ended up studying English Literature.

Because of her solitary upbringing, when she moved to Singapore, leaving her country and origins behind, she never had a deep nostalgia. However, when she started revisiting her memories through her work, she started recognising the exceptionality of that upbringing marked by a love for language and words, word play and humour and puns: “With time, the gap between language, literature and art started shrinking for me, and after some time I couldn’t separate the two.”

In Singapore, she studied at the Lasalle College of the Arts. This is also the time when S. Raoul, a fictional scientist and archaeologist, was born. Shubigi presented him to the world as her mentor, and her passport to hitherto inaccessible vaults of libraries and research centres. With it, she proved that the space of science, art and writing, and the nexus between these arenas was very loaded against women. Through books and pseudo-scientific theories, the artist had an excuse to teach herself archaeology and neuroscience. The whole process become the subject of her art.

How was your alter-ego S. Raoul born?

Adopting S. Raoul as a male persona was one of the first things I did when I moved to Singapore. He is really just me with a moustache. I worked under the name S. Raoul for ten years, because of this attitude I observed from my days in India, of putting art made by women in a different box. And I really disliked that spotlight, I disliked that we can’t look at an art piece without gendering it , which for me is really distressing. I think we should look content first. So although I was very idealistic when I was younger, I decided to never use my name, at least not for major works. Of course, you can’t keep a secret like that in Singapore, but it somehow it worked. The first artwork I did with this pseudonym was a reaction to disposable culture, and I reconstructed Singapore as if it was already extinct, based on the study of its garbage. For that project, I taught myself about archaeology, earth sciences, and geology.

I see this deep, passionate research behind with all of your work, so that in the end you can easily tackle these topics with experts in the field. I was wondering, why do you prefer to do all these studies as with artist an avatar, rather than doing it in the world, for example becoming an actual archaeologist?

Because I don’t believe in specialisation, in just learning about one field. We devote our entire short lives to pursue one form of knowledge. I can’t do that, that’s not how I’m built. If I was an extremely in-depth scientist in one particular branch, to sustain the hyperfocus required for that study, I would have to close my eyes and close my mind to almost everything else that’s out there. But I’m curious about everything. I have no affinities, I can’t say this bores me, you know. Okay, I don’t watch TV so perhaps I could find celebrity news boring. But even there, if I’d actually read celebrity news in-depth, I’m sure I would make something of it. That’s just the lens through which I look tat the world. I don’t think I could ever specialise. And I think it’s also a bit dangerous, because the best thing I learned from science books is that there is no specialised knowledge. When you look at nature, you look at the world. A naturalist is someone who has to be an explorer, and an artist and a writer. A scientist, an observer. If you look at Darwin for example, everyone knows of him because of the theory of evolution, but a lot of people don’t know that he spent nine years only studying barnacles.”

Having such a wide range of interests and also being very hands-on with the medium you decide to use, where do you start with a new piece?

I don’t have a particular starting point. For me, every single work is different, the approach is different, the idea drives the work, dictates my choice of medium, the poetry of material. Even when the words come out, I don’t think or plan before, I just start doing it, there’s no control over them. So, even when I make puns in the work that I may not be quite comfortable with, I still don’t erase them. I can’t make out which are the successes, which are the failures, they’re all the part of the mapping of thought. Because that’s the beauty of language. Even when improvised quickly, or not as well constructed, over time a sentence or phrase develops its own personality. It can stand on its own. Objects are like that too. That’s why in my work I use a lot of objects, because objects suggest a relationship, you have to do very little with them, they do their own thing. So like with words, I don’t have to think when I write, it just flows out. And that’s another reason why I don’t separate my text work from my art-making. I don’t see my work as visual artist and as a writer separate from each other.

When you tackle a new area of knowledge, you adopt the specific language of a field. Why this decision?

Because it gives the work gravitas and it anchors it in larger contexts and bodies of knowledge.. Most of the books that I found in my parents’ library were natural history books or old science books from the 16th to the 19th centuries, so I grew up with that sort of language. So it’s not an interpretation, it’s not something I pretend to do because it’s retro, vintage, or some such nonsense, it’s really how I’m used to reading and writing. Which is a bit of a problem, because I like simplicity. I really prefer precision in my writing, and I have to constantly stop myself from falling into that trap. However, it’s good to think and to understand the structures and epistemologies of writing as well, in history.

Coming from a different background but being a Singaporean artist today in your own right, what strikes you the most about the nation’s art and culture?

In my book about Singapore – made of my own photographs and some writing – I left two blank pages as a two-minute silence for the vacuums in our history. Because I really do feel that, that sort of truncated, abbreviated history, created a kind of break in contemporary art and the way it began in Singapore. So because this city is so global, many young artists are funded to go overseas and study to be recognised and to be considered credible. That’s how we could situate ourselves in a global contemporary context, in terms of art. So many of the artists born in 70s went to study abroad and then came back.

When you are offshore, you are placed within another historical context. When national narrative is the only narrative, and it covers everything else, political history doesn’t seem to work for you the same way in the history of art and culture. It’s about over-simplification. And the official national narrative began only 50 years ago. So it’s hard to move forward when you don’t know where you are standing today, and what’s rooted in the past.. I don’t believe in nations, in an easy way, but many artists feel the need to geo-politically situate themselves and their ideas. Not just visually, but also ideally. There’s been an advantage to that, which is why Singaporean art can always travel very easily, but at the same time, you won’t see much Singaporean art presentation in our neighbouring countries. So, you won’t see much contemporary Singaporean art in Indonesia. You won’t see it in Malaysia.

How was the situation, since you first moved here in 2002?

When I first arrived here, I felt there wasn’t enough criticality, and of course, I was a student then, so I was more hot-headed and less patient, let’s put it that way. When you’re young, you cannot wait for things to develop and to show their worth. I now recognise that some things need to be left aloneto develop, that’s all. There is lot of contemporary art made in Singapore and the quality of all the work that’s being made in last 10, 15 years is the thing that gives me the most hope. It’s not things like art festivals that make the difference, although there are always new ones coming up. You need to be able to believe that art-making can survive without all of that infrastructure

However, I have noticed that for the very young artists who are just coming out from art school, the art market is a big influence. What do you think about that?

That’s scary. I noticed a shift, a strong shift, in a lot of very young students in their late teens to early 20s, they’re very impressed with the arts fairs, for instance, and they think, “that’s the sort of work I have to do to be successful”. This awareness of current trends is okay, but it shouldn’t begin to dictate your post-art school explorations and processes. Here I find the financial support from galleries, collectors, patrons, and the arts council can become forms of validation or approbation. I think I was really wary of these external influences so for the first 10 years of all my work, I never applied for funding. At the time I believed in working under the radar. It’s not that I didn’t believe in applying for grants and such, when you apply for funding, you have to tailor proposals, and it has to work within current cultural policy of the country in question. For example, at one point there was a 40% emphasis on community engagement. Even if one could quantify that – which I couldn’t – the book that I was doing definitely didn’t have that appeal. There was no point in pretending that it did. Only when my works began to be appreciated, that’s when I gained the confidence to first apply for funding That was 2013, exactly 10 years after coming here.

Since 2013, you have been working on a project called “Pulp: A Short Biography of The Banished Book,” which is about the loss of libraries, as well as censorship and the power of the written word. You mentioned growing up in the beautiful library of your parents. Was it part of the reason you started this project?

It’s difficult to talk about it… My parents had what is possibly the best collection in South Asia on rare books of natural history. Of that library now, we have maybe a handful of books left. Everything is gone. The first time, we were robbed in the 80s, and the burglars didn’t realise the value of the books, they just destroyed them. They ripped the covers of the pages and sold the papers, like trash. The second time was in 2013, when my father died. My father had been living very far from our home, in the mountains. By the time I reached him, the library had gone again.

Those books were immensely valuable. I’ve seen them to end up in auctions. For us, we never saw them as objects of value. My parents were not rich people, but they spent all their money going to all the old auctions, where people who didn’t know their value often sold themby the kilo. Many books came from the British officers and tea planters who had collected or inherited vast libraries. And then when they died, their descendants just wanted to sell these books not knowing their real value. I remember as a child going through those stacks of old books piled up, and I’d always find something to read. So, it was very much part of our family’s culture. You know, the things that bind the family together, like eating for instance, or cooking together, or travel. For us, it was always books. The love of neglected, forgotten, discarded books. So, to lose them for me was a great grievance. I miss it like I’d miss my own family. We’re not going to have that knowledge, that is gone with my father. My father, my mother, the only thing they had in common were these books. And, their combined knowledge is what made the library so special. It was a library of literature, of nature, and of old sciences looking at the world. There were also religious books in the same bookcase as the books on mythology. I grew up with the writing of people and populations that don’t exist anymore, because now they’re extinct. So, to me, that’s humanity, that’s what it means to be in touch with the humanity. The loss of that library meant loss of that personal connection with humanity.

Is art for you a way to give a new shape to that lost library in your heart and reconnect with humanity somehow?

You know, I make art not just because I’m interested in books, or because I like books. It’s very personal. And books are not the information they hold. Books are the voices of people long dead or gone, people you would never meet because of time and space. So, a little Indian girl growing up in Himalayas read the words of people from centuries ago, or continents away… it didn’t matter. All that geography and time collapsed, it didn’t matter. I could be connected to humans talking across the ages. And that is what drives my own art-making.