THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 20

Zihan Loo

At the end of 2015, I was wandering around SAM8Q looking for the proverbial exit through the gift shop — as Banksy would put it. I wanted to buy some books to bring back home with me. At the ground floor of the building there was something that appeared to be what I was looking for. Shelves of interesting books, and a few on exhibition. I was thrilled. When I walked in, something was not quite right. I asked the person at the desk: “I’m sorry, this is not the museum bookshop, it is an artwork.”

Damn! This is precisely what I’m talking about when I speak of the problem with contemporary art. The work, he explained, was done by artist Zihan Loo, and was called “Of Public Interest: The Singapore Art Museum Resource Room”. The artist moved 4,500 volumes from the Singapore Art Museum’s resource room — currently not available to public — into the space of a gallery. The public were invited to shape the collection for the duration of the exhibition from August 2015 to March 2016. The conditions were that each visitor was allowed to withdraw one book from the collection, restricting the public access to this book for the duration of the exhibition. These books were shrink-wrapped and placed in a separate area of the installation.

Also, visitors were allowed to loan one book to the collection. This contribution was in effect for the duration of the exhibition. These books were accessible to other visitors and placed in a separate area of the installation. At the end of the exhibition, there were a total of 84 public withdrawals and 14 public contributions. These interventions, along with a form that lists their name, gender and the reason for their withdrawal/contribution of the title are archived below.

The bureaucratic aspect was evident in the work, together with a team of twenty-five volunteers. These books were catalogued and sequenced chronologically according to their date of publication, and colour-coded according to the location of the publisher and presenting institution. The type of books the museum decided to collect reflected the priorities and concerns of the museum. As for the intervention of the visitors of the installation, it showed the problematic relationship between audience and the museum, and how these mutually influence each other.

The name of Zihan Loo kept on popping out every time I talked with other artists about the theme of censorship, which is one of the myths surrounding Singaporean contemporary art. We all know that oftentimes myths are based on reality, so I was keen to gather informed opinions of this form of “subtle censorship”, as it was experienced by Singaporeans.

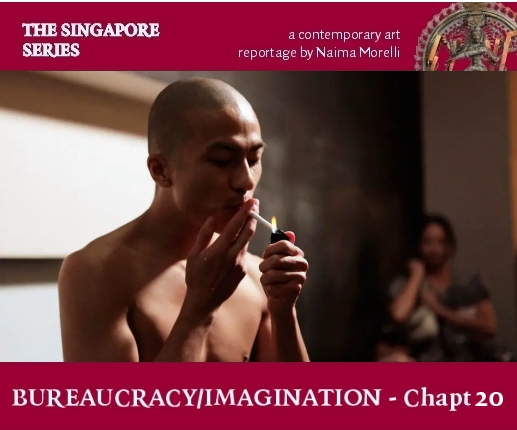

Presented first in Chicago and on the evening of 19 March 2011, at the Defibrillator Space in the West Side of Chicago, he stood and read from a text, an affidavit written in 1993 by Malaysian-based artist and documentarian Ray Langenbach. It was an eyewitness account of a performance by Josef Ng entitled Brother Cane. After each reading, he performed what he read. The act was broken up into segments of time, alternating the reading of the text with the actions off the page or Josef Ng’s movements as described by Langenbach. Why did he choose to perform Brother Cane in Chicago?

The performance was then represented at “The Necessary Stage” as a Fringe Highlight for M1 Singapore Fringe Festival 2012: Art and Faith, the performance “Cane” draws from the 1993, Singaporean artist Josef Ng’s performance of Brother Cane which resulted in a public debate over obscenity in performance art and led to a ten-year restriction of the licensing and funding of performance art in Singapore from 1994 to 2004. Josef Ng was charged in a court of law for committing an obscene act and he pleaded guilty. He was fined SGD $1,000.

Cane consisted of six testimonials of Josef Ng’s performance, which seeks to both reconstruct and fragment the memory of the event. These six accounts are namely: The media’s account — the artist read excerpts from twelve newspaper articles covering the performance and its aftermath. The eyewitness account — the artist invited Ray Langenbach to read his eyewitness account of the performance which was used in Josef Ng’s trial as an affidavit. The re-enacted account — a screening of video documentation of a re-enactment in Chicago based on Ray Langenbach’s eyewitness account.

Like many other artists in Singapore, Zihan Loo took multiple paths and multiple roles, being at times an artist, an actor, a director. His short film Threshold was the first one which he entirely directed by himself, whilst Solos was co-directed with Kan Lume. “Solos was a good learning experience. It was the first time I was working with movie contracts, dealing with production budgets, , and travelling to present and defend the work. People don’t always understand that the director is not the only person with a say. There is the producer too and many other individuals with vested interest shaping the film, it becomes a collective decision. Solos and Threshold are the lessons and after the experience of working on both films, I arrived at the conclusion that I preferred to do smaller works. I realised that work doesn’t have to be so long, it doesn’t have to involve so many people, and I would rather work on more intimate essay films or shorter films that are a little bit more compact and within my own means. So I retain a certain artistic control over the final product. \”

I arrange to meet Zihan Loo, who asked to meet me inside the installation “Of Public Interest”. Perhaps it was the setting, but I found that the entire interview was very bureaucratic in the way it felt. Zihan Loo was very professional. Open but somehow detached, and I couldn’t really build a connection the way I did with other artists who I had the chance to meet at home and in cafes. Between the lines, I could read a vulnerability and but also a defence. It might be a partial analysis, but I find that conflicted attitude in many homosexual artists in Singapore: the willingness to share what is true to them — and sure thing, Zihan Loo has been very forward in that — but also the knowledge that you must be guarded in a country where homosexuality is still prohibited by law.

After a few questions, Zihan was distracted by a person that entered the installation looking confused. Zihan giggled: “It’s so strange because people would come and think this is a conventional library and they go, I want to see the work! I want to see the art! Where is the art?”

“That’s what I thought when I walked here, I though wow, here’s the book shop, I can finally buy some catalogues!” I said

“Yeah, we have a lot of visitors like that! It’s part of the installation. It started in August this year (2015) all the way until March of next year. I’ve never had an installation on for so long. The extended time was very important from the onset and it has to keep evolving, so every time people come into the space they would see something different and that’s why the withdrawals and the contributions are very important aspects of the work. The participatory aspect allows the installation to evolve, so it does not remain static. The way I have arranged them is kind of logical, according to geopolitical regions (there were five main categories — Singapore, ASEAN Regional, Asia Pacific, International and Journals / Magazines) because that’s the way I can review certain gaps, or a certain lack in the collection itself. Hopefully that’s immediately visible to a person who is critical of the collection and the institution.

What is the reaction you would like people to have towards your work?

I don’t choreograph it so much. Ideally people would withdraw a book because they disagree with the content but as I discovered, people agree with the content and they withdraw the books because they like the book or the artist and they would like to isolate and highlight it.

Indeed that was my first thought when I walked into the installation. I thought you could withdraw the books that you like, but then other people talking about the work explained that you could censor a book.

Yeah, and it is also experimenting with these things are unknowns or untested. . As an artist, you always have it mapped out very clearly on your mind but until you open it up and welcome an audience to experience it you would not be able to gauge how they will respond to it.

Because “withdraw” as a word can be interpreted

I wanted to leave it ambiguous. I didn’t want to say “censorship”, or “removed”. I wanted to give it a word that was a little bit more ambiguous and see how people responded to these terms of engagement. And people have recognised that yes, when you withdraw a book and you isolate it and you put it on display, it draws attention to the book itself, which is part of the paradox of censorship . The main difference is, unlike an anonymous act of censorship, members of the public have to associate their names with a certain book, and provide a reason for the withdrawal, so they are held accountable and associated with their withdrawn volume.. This resource room is a portrait of the institution and the institution’s history and the section with the withdrawn and contributed books on display is a portrait of the audience that visits the institution. I am interested in who comes to the museum? Why are they here? What sort of people are they? What do they think? How do they behave? And the withdrawal and contribution aspect of the installation actually reveals more of what the audience is like and their interests.

What does the installation say about the museum and its role?

It is also keeping the museum contemporary, because I think now the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) needs to be [at the forefront of being a contemporary art institution]. SAM is being compared to the new National Gallery of Singapore (NGS) that opened in 2015, both institutions have an interest in representing canonical modern art and contemporary art. So alongside the NGS, how does the Singapore art museum reposition itself without both institutions duplicating each other’s interests? How does it remain contemporary? This requires them negotiating with works that challenge the conventions of how art is experienced and displayed . I’d see this work as a challenging work for the institution to stage as it challenges people’s expectations of what contemporary art is.

Zihan describes himself as fortunate to have came from a family who was supportive: “Since I was very young, they were sending me to art classes and music classes. I guess that is the case with a lot of Singaporean families who are upper-middle class. I wouldn’t say that I was particularly talented.”

Zihan applied to get into the Art Elective Program in secondary school — a specialised art educationthat only certain secondary schools offer — and he got rejected. So art hasn’t been a big focus during his JC (junior college) and secondary school. After he left JC, he started becoming more involved in theatre and went into lighting design. From there, he got involved with visual communication and graphic design.

Then he decided to go to university to pursue a degree in fine arts and from there he went overseas for his MFA on video and filmmaking: “At the same time, it was in Chicago that I started to do performance. I have always been kind of involved in performance, having performed in my own films in the past and I was also involved in theatre. There has always been a performative aspect in my work. But the first time I did what you would conventionally call “performance art” was in Chicago, it was from there that I developed. Chicago was also where I started the practice of re-enacting — the practice of revisiting old works, re-enacting an archive.”

That Chicago phase was important for you, it seems. Why?

I was free to do a lot of things which I wasn’t able to do in Singapore. The conditions there were more appropriate. It wasn’t Chicago itself, it was also the fact that I was alone in a foreign country and there was no expectation or baggage. I was free to reinvent myself and be somebody else or to construct my own history and my own background. So that was also part of the reason, together with the school which was really good. I wanted to go into experimental filmmaking, so I decided to do a MFA in film and video, but of course, things took a different turn when I went to Chicago.

It’s interesting how your work is composed of two movies, a few short films, theatre. You are the intersection of many worlds. Do you still work in theatre?

Yes, I still work as a multimedia artist, designing content for theatre productions. I work closely with The Necessary Stage, a Singaporean theatre company. Conversely, I don’t work as much in film anymore. I have since moved away. And I’d say it’s because of the funding structure in Singapore, because in film the funding body is less open to experimentation. They still want a conventional narrative structure , they still want the blockbuster films, and those other projects that they will promote, there is a limit to experimentation. It was very difficult to get funding for experimental films. And with the National Art Council, the funding situation is a little bit more open, they are more willing to fund experimental theatre and performance. So indirectly, the funding structures in Singapore shaped my practice. You are made to consider how you position yourself as an artist to benefit from various funding structures. It is a strategic positioning. It was also not a deliberate and conscious choice, but in hindsight, that was what happened.

You mentioned funding. I see that for younger artists who are coming out of school today they immediately enter the funding system. Was this scheme already in place when you came out of school?

Very much so. Even before I went to Chicago, there was a certain awareness of the funding structures already in place. I think us Singaporean artists are quite coddled by a state funded grant system. The government is very supportive, but they are very supportive only of a certain kind of work. We would like the government and funding bodies to be little bit more open to a variety of works. At the same time, we understand where they are coming from and why they are conservative with funding experimental work. But what I think is also lacking is audience, spectatorship, the maturity and ability of the audience to defend and support the artists and the work the audience personally believes in. Another thing that is the lack of private sponsorship, corporate sponsorship. The responsibility of supporting and growing an art community should not fall on the government alone. I think artists, audience, and the state ought to look to the government for support. And hopefully the community matures so that both artists and the audience will take on more of the responsibility over time.

So you feel it’s mainly about time? Do you feel that the art public is quite elitist here in Singapore?

I think anywhere where the art is a bit more experimental it will appeal to a very niche audience. I would say in Singapore, the problem is not that it is niche or elitist, because as much as there is elitist work out there, there is also the socially engaged, community based that often is overlooked that we don’t discuss it as often. But I think the problem is the passivity of reception . As I mentioned, the willingness of people to stand up and take a position to defend the artwork, or to criticality engage with a work. To look at the work and understand why they like or they dislike the work and be able to support and voice that views. I think it is this kind of critical spectatorship and critical eye that is lacking, because of the lack of art education, or the lack of focus on art education in Singapore. It has never been a huge part of our education system.

I think that when it comes to contemporary art, that is valid in most places. In Italy for example there is a good education regarding ancient and modern art, but you definitely have a lot of scepticism for the contemporary.

I’m not even addressing contemporary art. I’m referring to a basic art education that engages with ancient civilisations or modern art, not just in the West but also the East. That foundation was never discussed or established within our pre-college education. The National Gallery of Singapore is the first time that these works, the modern Singaporean and Southeast Asian works have a permanent exhibition home. Prior to that, it has always been temporary exhibitions in various art institutions (state-funded, operated or otherwise), you know? And that is indicative of the state we are in, in terms of establishing a canon or a local history or regional history and the dissemination of this information to the next generation. It is only now, with the establishment of the canon at the National Gallery of Singapore that this particular generation would have that kind of exposure, that kind of resource to tap into. We are at a threshold now as we negotiate with history and that’s the situation with Singapore. To add to that, there is also the additional problem of how the “modern” and the “contemporary” in Singapore happened at the same time. We have had such a compressed history where there have been rapid advancements in certain sectors, but the lack of advancement in other areas.

And what are these areas?

Aside from the aforementioned art education, the artists are developmentally at a different stage as compared to their audience. So artists find themselves in a situation where we are not sure if we should proceed with our experimentation or worry about alienating our audience and constituency.

Is that something you take in account yourself when making work?

I struggle to, and I just had this conversation today. Basically I’m preparing for an upcoming experimental theatre production, that takes on the form of a dance lesson It requires the audience to commit over a period of three weeks to take a class and to participate in the dance class.

Oh yeah, I saw that on your website, it’s called 50/50 right?

Yes, basically I’m playing with the concept of an audience going to theatre and experiencing the piece as a passive audience and getting to engage on the very cerebral and also physical level of the production itself. But the signup has been very, very disappointing. People are afraid. People feel uncomfortable if they participate. Should I not do the work because the audience is not ready? Or should I proceed with the work, but have nobody coming up to watch the show. So what do you do? The problem with producing such a work in Singapore is that there isn’t the audience to support it or willing to take risks with an artist to support them.

Can you tell me about your 50/50 project?

So basically I’ve been doing a social dance, which is Lindy Hop swing dancing for about 15 years. I performed, I have travelled and attended swing dance camps. It has always been a hobby, I have never incorporated it into my practice and I always wanted to so this series of dance classes that will be taught with a co-teacher, so every single class has a different collaborator. And each class will have a different focus. The first class will be investigating gender roles, the second class will be investigating ethnicity and race, and the third class will be investigating sexuality. Because Lindy Hop as a form of dance is very traditional. So the guy is expected to behave like a gentleman and the lady is always a lady, and there are very normative and prescriptive roles. It is also complicated ethnically because it started with African-Americans, then it got adopted by the Caucasians in America. It was popularised by them and they are imitating African-American gestures. That way of clapping which is also associated with Black transatlantic slavery and that was the origins of the dance. Then now we are Asians learning this social dance from Americans or the British , who adapted from African-Americans. It is very interesting in terms of performance and performativity. These layers of drag from a queer perspective, the putting on different guises. The third and final class is investigating me as a gay person. Why would I be attracted by this very heteronormative kind of dance, where it’s very much about seduction and connection between a male and a female? What is it about this that appeals to me? So breaking this down in a dance format, and getting people to dance and connect and perhaps changing and switching roles. That is the intention of the piece.

So did you find out what appeals you to this particular kind of dance?

I’m still trying to find out, that is why I am embarking on this production. Essentially it sounds very cheesy, but it’s the connection between two individuals, and as a queer person it was an excuse for me to learn how to be intimate with the opposite gender. I never had the safe space to know how to hold a woman. How to be intimate with a woman in that kind of safe non-sexual way. And Lindy Hop allowed me to do that.

It’s like the roles were already set and you just had to learn the steps.

It allowed me to perform and pass off in a very heteronormative structure under the space of the dance. There wasn’t the threat of Salsa, which is more sexual, or Tango, which has a vpassionate sexual energy. Lindy Hop is happier and more uplifting. . But that’s in hindsight, of course when I started the dance I didn’t know why I was attracted to it.

Your homosexuality is something that comes out during the course clearly from your work, and you state it also as the first thing in your bio. Did you feel it was important to specify that?

My work has always been autobiographical in a way, whether explicitly or implicitly, so since the very first work, my sexuality has been part of it. I don’t see any reason to hide it or disguise it, I see that as part of what I’m trying to do with my practice, to get people to see differently or to have alternative ways of experiencing something. It wasn’t always like that. In the beginning I was a bit hesitant about putting that informationin, because at the same time I didn’t want to be labelled or pigeonholed by it. But now I’m much more comfortable, because people have seen that there is a variety with what I do, so it’s not just about queerness, but it is also about archival and re-enactments. So I’m okay to have it stated quite clearly. I don’t think there is anything to be shameful about, but I understand why people would be reticent to talk about it. Because people do classify and group you into a certain kind of niche when you proclaim that you are queer. I’m still negotiating, even though I am comfortable at this stage.

Much of your work is very personal, but also involves other people which are part of your story. How do you deal with the fact that other people are in the work?

Obviously my family has been supportive. If not, it would not be the film. It is hard to say. Seeking consent is always very important from an ethical point of view, it is basic understanding, getting permission, even before the work is released. Whenever I involve my parents or people that I am intimate with, in the work itself it has to have some level of consent. I try to make it understand that in order for more a complex kind of representation, it can’t always be favourable or positive, it requires both aspects. For example, when Autopsy first came out, my mother was a bit resistant but she saw how people responded to it. So people after watching the film would come to her and talk to her about it. And for her, that kind of experience was important. That insecurity in the beginning, but then seeing how people responded to it, the opening up and building a certain trust, so she is open to my work in the future.

How was your work when you were first starting out, back in school? Was the seed of what you are doing now already there?

Yeah, Autopsy the film was actually done during my school years. It is a conversation with my mum. It is not my favourite work, but it has always been received as an impactful work. But I remind people that it is the most manipulative work of mine, it is structured as a very conventional essay documentary form. I shaped and edited it in a way to have a certain kind of intended impact. That is primarily why I’m not very satisfied with it. For a certain period of time, I was producing work that had that kind of manipulative deliberate quality to it, where I wanted people to experience a certain journey and react in a certain way, and now I would like to keep it a little bit more open and ambiguous.

How does Autopsy relate to your autobiographical movie “Solos”?

Everything after Solos was in response or relation to that experience that I had with Solos. So Autopsy was a counter-narrative in a way. Because in Solos, the character that plays a mother figure does not speak. She was this voiceless character walking g around and in direct opposition to that depiction, in Autopsy she never stops speaking, she is vocal and activating that kind of absence that was in Solos. That is a very clear example of how the work after Solos was an extension and development of Solos. But it was a good experience.”

It is always difficult when it comes to personal work. In Autopsy there is a sentence spoken by your mother, telling you: “I trust you, if you are sure of what you are doing”, something along these lines. I’m wondering if you have ever struggled with self-doubt, since you put so much of yourself in your work.

Yeah, always, constantly. I think it comes out in the work as well. The duality, the duplicity. I constantly undermine or question what I am doing. And hopefully it comes out in the structure, because that is part of the process of creation. I am never absolutely certain. Even with this installation, there is always a sense of fear. Fear of whether people would get it, how people will respond to it, but that kind of ambiguity is interesting.

So your doubts are about people’s reaction to the work, you never question why you are doing this or the importance of the work.

At this point in time I am much more confident, but when I first started, especially with Autopsy and the earliest work, there was that sense of self-doubt. But over the years, with this installation (Of Public Interest: The Singapore Art Museum Resource Room) in particular, it is a stripping away and getting to the essence. It is removing. My work is more clean than it used to be. It used to be a bit too embellished and now I’m stripping away the layers and just trying to get more essential without being overly reductive.

I really like that sentence that you have on your website, that you are trying to reconcile the flesh of the performing body with the bone of the archive.

That is not an original observation by the way, it comes from Rebecca Schneider’s Performing Remains article. But it is important to read and it is important to reference theory . Rebecca Schneider has been pretty influential in my work, her writing on reenactments and performance and what remains after a performance ends. Have you seen Future of Imagination?

Not yet but I’m planning to go.

This festival is very important in our art history. Because it was the first performance art festival that received a licence after performance art was restricted for ten years, since 1998. It was with Future of Imagination that the licence was approved again and has been going on since then.

Talking of performance art with Zihan Loo, we inevitably ended up taking about Cane. I told him that one of the things that struck me the most was the fact that by re-enacting the performance, he was creating a connection between the artists from the ’90s and his own generation of artists. It gave me a sense of continuity and solidarity which one would deem natural in such a young scene.

He explained that the lack of fluidity was also dependent on the restriction or licensing of funding. That cut off one generation of artists that were the mid-career artists. Those who were established by the time the performance came about and were not affected by the lack of funding, and they continued to perform. They would be invited overseas to festivals. Alternatively they would perform underground, because they had a safe space that they established themselves.

The younger generation however, who were trying to get into performance art, moved away and got cut off. So in performance art, there was a gap in terms of conversation or larger consciousness. Within a group itself the conversation continued, but people were not allowed to publicly discuss and present about what they were performing. Zihan told me that this kind of void was around for ten years.

“The reason for my re-enactment was coming back after these ten years and thinking about where to pick up from. What is performance in Singapore today? And do we sustain this conversation with this perceived gap of ten years? So for me, I don’t see it as productive to be creating new work. I also don’t consider it to be as productive as continuing the tradition of that kind of very actionist , gestural performance art and I wouldn’t call myself a conventional performance artist, because I don’t do gestural type of performances. I did try performing perhaps once or twice, but I don’t see it as relevant to my practice. So I only perform these gestures when it is in reference to re-enactments.”

Another thing you say is that you are trying to recuperate the public memory of these events…

Recuperate or complicate? At this point in time I’m not so sure. Because every time you talk about it, it confuses the memory, when we recall or retell the oral history of something in the past, we always rewrite the history in a certain way. But I’m also conscious that my role is to provide multiple accounts and the audience itself has to draw their own conclusions or draw up their own narrative based on multiple representations. It is problematic when one single account becomes very authoritative, one single voice becomes very dominant. My performance was constituted by six accounts. Six different points of view.

Another angle I’d like to talk about in reference to “Cane”, is the fact that when you re-enacted the performance, you were working within the current restrictions of performance today, where there is no more ban, right?

The ban on performance is not there as long as it is scripted. Today performance still has to be scripted, and you have to submit your script for vetting. That is a paradox, because performance art thrives on spontaneity. It thrives on reacting and being in the moment, and the fact that it is scripted in actually is an antithesis of the spirit of performance art itself. So my claim, which is controversial, is that performance art can never exist in Singapore, because everything has to be scripted. Even when we allow performance art again, it’s not really performance art because we are always in fear of deviating from a certain choreography or script that we have set in mind for ourselves. Whether it is in a paper we have submitted to the arts council or whether it is written in our mind and we have to account for it, there is still that fear, that censorship within it.

In this sense, you have to perform according to a script. This makes you a lot like a film director, which is a position you also were into.

That comes from my background in theatre, so there is always a negotiation. You know there is always this tension, it is either theatre or performance art, it exists between these two polarities. And I see myself positioned in between, perhaps complicating both. So it’s not exactly theatre and it is not exactly performance either.

What is said about censorship is that the government is just embodying the will of the people. Have you found some truth is this claim?

From what we have observed from recent years and also what is happening with Cane, it is this feel of multiple accounts of history. The government desires one single narrative, one clear authority. And artists provide multiple accounts. We see this in Singapore, we provide alternative histories or an alternative past. Alternative ways of remembering. In a small country like Singapore, the government sees itself as controlling or consolidating power when it has the singular narrative and it is this fear of artists disrupting the singular narrative that is the root of a lot of the censorship.

Does the way censorship operates change over time?

Yes, it has evolved and matured. It used to be much more simple and direct. Today it is much more layered, it is for our benefit but it is also detrimental because a lot of the censorship gets internalised. A lot of censorship gets diffused to not the State but the curator or middle-level management. It is not so much the state itself, but the institutions who are protecting their own interests. State funding comes in and institutions have to be comfortable with that. So it is less direct and less clear compared to before and it’s much more insidious. It happens, but it’s not visible, it happens behind closed doors. It appears on multiple levels at various stages. It is just the way the world has evolved.

In general, I have found the three main reasons to censor something are politics, sex or violence. Do you find this to be true also in Singapore?

Singapore is much more tolerant of violence than sex. I think that influence stems from Hollywood. Sex does ruffle a few feathers, but I think out of the three you have listed, the censorship for what is considered “political” is the most conservative. So thet political reinvention of history, reclaiming of history is very much frowned upon, then followed by “sex”, then followed by “violence”.

And maybe sometimes there is a connection between the three. For example, I saw that in Indonesia nudity is censored in order to appease Muslims — the real reason though is mainly to manipulate that part of the population for political reasons. It’s an instrument of consent.

But in the region, there is a lot of self-policing and community policing that happens. In Singapore it is still gravitates towards a top-down authoritative approach to censorship. And what artists and community are trying to encourage is this kind of ability to let the audience decide, or to let people decide for themselves, what they would like to watch or what they would like to be exposed to. And I think that’s the stage that we are working towards. We are not calling for abolishment, I think it is idealistic and utopian. It is impossible. Censorship has to happen in every society, it is just the way society works. We are asking for akind of dissemination of power in a way, or a fragmentationof power so it’s not coming just from one government agency. Letting the audience decide for themselves what they would like to experience and witness, giving them the autonomy to do so.[i]

Addendum:

This interview was made in one session between myself and Naima Morelli on 26 November 2015 when she visited Singapore. This interview was a casual conversation, on record, at my installation space that was designed to emulate a reading room where knowledge is shared.

The version you have here was returned to me transcribed approximately three years later. There are sections in this transcribed interview that I find ambiguous without proper context or framing. I have attempted to amend some sections of the interview from my 2018 perspective, looking back at myself in 2015 and trying to imagine what I meant. But despite having done so, I would still like to urge you to keep the fallible nature of memory and the duplicitous nature of representation in mind as you access this text as a resource.

I welcomed Naima into my installation with a spirit of generosity and good faith that an artist offers to an interested member of the public who possesses interest in the artwork and my practice. It in in a similar spirit that I am writing this short addendum and engaging with this transcribed interview.

As mentioned in this interview, there are always multiple versions of the past that exists, and this is one version that was recorded and represented over time through Naima’s lens.

Loo Zihan

19 August 2018

New York City