THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 19

Funding Shaping the Work of Artists

Let’s go back to The Substation for a second. We mentioned that when the space started in 1990, it was the very first art space in Singapore, before SAM, before the Esplanade and much earlier than the National Gallery. In the narrative of the local art world, the existence of this place encouraged many people to gather to appreciate and make art, music or writing in a way that couldn’t be found anywhere else in Singapore. This was a sign for the government, who acknowledged the situation, observed a spontaneous surge of creativity and cultural momentum, and decided it was high time to open up an art museum five years later. “We were actually forcing to government to shape policies in some way last time,” said Alan Oei during our conversation: “But once they shaped the policies, we kind of have been sucked into their policies and we haven’t made them change anything for a long time.”

The nostalgic tones in which Alan Oei described the past of The Substation abruptly changed when we moved on to talking about the present situation. “I think the rate of production in Singapore is fucking ridiculous,” he said with contempt. “It’s like the museum has a show every month or something”. The The Substation’s director sees the art space’s quick turnover being driven by the government. In this way, the measure by which we say a show is successful is the number of people that go there and the number of programs. I feel the shows are not properly researched and curated and they are just doing a lot of programming. And it’s not that they are not thinking about the older artists like TAV or whatever, it’s that they have run out of artists.” In his view, Singapore doesn’t have enough artists for the amount of shows and the amount of programs that the government is trying to push.

I asked Alan if the institutional and the independent worlds ever meet, like what often happens in emerging art systems with independent curators also working for big institutions as well as commercial galleries. He told me that he thinks there is quite a number of independent curators. However, these can be found working also for museums, as well as making shows for galleries and independent shows. “Just like we don’t have enough artists, you might say we don’t have enough curators, or too many curators.” I interpreted this as not being enough for a voracious art system, but too many if the system was healthy.

“That’s why there are so many artists, because it’s easy, there is a need. We don’t have enough artists, so the government is putting money up there, so obviously you meet a lot of young artists that want to do something. And we don’t have enough content, so to speak. That is why a very young guy at the age of 25 might be doing a show in the museum already.” He saw that the problem with both artists and curators is that they end up not being very good, or not being able to do their job properly, because the existence is secondary to the structure that needs them. They have in that, the aforementioned function of Queen Elizabeth. “The government is very good a doing buildings and festivals. We must have artists to fill it all up.”

To him, The Substation too has fallen into the trap of producing content on demand. “That has been the problem. What we want from the artists rather than what the artists have to say to the rest of the world of Singapore. And it has been just trying to do so many programs for no reason, other than the fact that the government gives us grants based on our programs, and that’s a huge problem.”

“I feel now it’s a different time. We people feel we can say something back to the government, we want to change our lives, that Singapore doesn’t belong just to the government but to all of us and we can shape our own lives. I feel in this time of change that I don’t know where our artists are. Most of our artists are more interested in Biennale and museums and art fairs and their career and are not interested in saying, “I want to be part of the cultural change in Singapore.” So whether with Open House or The Substation, I want to find artists who care.”

Indeed, as director of The Substation, Alan intended to go back to the original spirit of art making in Singapore. He wanted to look at the artists making stuff that is really important and relevant to the lives of Singaporeans. “I will look at how they would shape or encounter the world, what kind of ideas are being giving to challenge the status quo. We no longer have this big building, we have to fill it with a lot of things. There are artists out there who are doing very interesting things, let’s find a way to help them. I guess that’s a very big conceptual ideological shift in terms of thinking about what The Substation can do differently.”

“Hopefully that will happen”, I said cheerfully

“It better,” said Alan in his peremptory attitude, “If not, we should close down.”

Funding is a vector of the art production

Many artists I had conversations with weren’t afraid to clearly tell me of the impact of the funding structure in Singapore and how it has shaped their practice. Artist Zihan Loo told me this clearly during our interview: “It is strategic how do you position yourself as an artist to benefit from various funding structures. For me it wasn’t very conscious, but in hindsight, that’s what happened.” Zihan Loo, who works across different media, found that the funding body for film is less open, wanting conventional narrators and blockbuster films. “It’s very difficult to get funding for more experimental films. With the National Art Council, it’s a little bit more open, more willing to fund experimental theatre, experimental performance.” He wasn’t the only one acknowledging the impact of cultural policies on his own work. Artist Heman Chong – who like Zihan Loo is also pretty passionate about the restrictions the government puts on art and individuals’ freedom – also talked about the subject on the pages of Asia Art Pacific: “Looking back, my entire journey as an artist has been heavily assisted by cultural policies, which have produced the institutions that have served as cornerstones in the evolution of my practice.”

There are also those who are wary of the restrictions coming with government funding. Eugene Soh is from a younger generation compared to Heman Chong and Zihan Loo, and described getting funding from the government as suicidal: “I have my opinions about it. When I meet artists in the art scene, I feel like in Singapore we are still with our parents. Even if we go overseas, our parents will pay for our flight and everything like the Amsterdam trip, our flight was paid by the National Art Council, the government and a lot of big bodies that pay for us. Oh, we are still kids getting paid by our parents. Compared to the art scene overseas, I don’t know if it is true or not but they kind of self-sustain. They have moved out of their parents’ house. If you get money from your parents, you don’t want to talk bad about them.”

When there is an opportunity, you must be able to have self-control and use it wisely, not just becoming dependent by it. We see today many young artists working only if they will get the funding. In addition to that, government grants are often times project-based. This is not bad if you think of art as a job – as is always the case, as I pointed out earlier. However, it shows a lack of personal initiative and sometimes even a lack of that primal urge to create, that ideally should compel the artist, where the return in cash is only an afterthought.

I talked about this in 2015 with Ben Hampe, the former founder of the defunct Chan Hampe gallery, who told me that he said that he trained the artists he represented to not rely on government funding, but to do work that will sustain them instead. “There is definitely a group of artists who rely on the government pay check and they would create work in response to government grants. It creates this sense of entitlement and similar work.” The gallery itself didn’t take government funding, except for expensive international projects. And then there is the infamous censorship problem: “Singapore has censorship and the government would give grants only to artists meeting certain specifications, and if the art doesn’t meet government’s needs, they cancel the grant,” said Ben. “It’s a carrot on a stick thing”

Bala Starr, director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore at LASALLE College of the Arts, is accustomed to the Australian art world where a system of government funding of artists and organisations is long-established, although support has been diminishing in the last few years. She sees funding for artists as key, both for the individual and for a developing art scene, but doesn’t see it as a simple answer or solution. “It is challenging for artists to fully commit to their practice if they have a full-time job,” she commented. “The government funding is instrumental,” she continued with her gentle and passionate voice. “But I had an artist approach me at an exhibition opening recently, saying: “I’ve got the money, I just don’t have anywhere to show the work.” That didn’t make sense to me. I’m sure the National Arts Council has also long been questioning the quality of projects, how they promote an art scene, how a government can best encourage excellence and experimentation without being too broad, funding everything. How they can make very careful decisions while still being generous and stimulating creativity. It isn’t easy, but I wouldn’t say there hasn’t been enough public funding here.” I asked her if excessive funding can do more harm then good. She goes back to the question of why artists make work: “Art requires resilience of an artist. It requires fortitude, it requires some solitude. It’s a difficult profession at ground level, we know that. But I think the better artists are asking these questions about sustainability of themselves. Government funding is not itself fundamental to enabling an artist’s practice.”

Education and institutional recognition

Bala Starr observed that institutional recognition is something that has become very sought after, in Singapore and beyond. In her native Australia, it has translated into the popular pursuit of PhDs in art practice in the last decade. “You have so many artists with higher degrees but you don’t hear an argument that the quality of the art has improved in that period. It’s about a big institutional machine, about government, and about economics. You can feel that here in Singapore too. Even without the PhDs. It’s also the fact that people here find the authority and the conventions of the academy very attractive.”

Jason Wee of Grey Projects also acknowledges that Singapore spends a lot of money and time on the arts, but this money however ends up in big institutions and in building schools. Its interest in creating art professionals shows up in the way it has created an arts high school, it has encouraged the existing art colleges to develop graduate programs for the art. The result is that today in Singapore you can study art from the age of thirteen from high school, get your first degree, get your master’s and can now get a PhD in art history if you like. In addition to that, there are also a few graduate programs and there are a range of them that are interesting to artists. You can get a master’s in writing now, even art writing. And then you have art museums, then you have art fairs, but between schools and the museum and art fairs, they only encourage galleries.

“If you look at what the state funds, among the major companies, there has been no visual arts major company in something like fifteen years,” points out Jason. “There is only a multi-disciplinary space which is Substation involved in all the arts, and then there is an educational one, whose work is mostly for school children below twelve. But the major companies in Singapore are the symphonies, the major theater companies, the Chinese orchestra. So I don’t think it is that healthy for artists to graduate and only have galleries and then have museums and art fairs right after that. It means that the system is going to give you certain rules to play by. And I think this would be detrimental to Singapore. Indonesia is not like that at all. Indonesia has a lot of artist-run spaces, a lot of artist initiatives. I think this is one reason why those scenes are interesting. Not necessarily because they have a bigger market.”

The usual comparison with the big art market of Indonesia often comes up. This is a country which doesn’t have any state funding at all and yet has a lively art community, a burgeoning art market and it is the forefront of the contemporary art developments in Southeast Asia. I asked Jason if he sees it as good to have funding at all at this point.

Jason admits he asked himself this question several times. He knows that people from the region are often very envious of funding in Singapore. “But for us it also a trap, a curse, a problem that Singaporeans get too comfortable with. Because when artists have funding, they just do what is state-friendly and market-ready. They only rock nostalgic boats, they don’t want to criticise the state, they avoid systemic or ideological critique altogether. And there are actually artists who say in interviews that they don’t want to talk about politics.”

I point out that perhaps it also depends on the context. If you were to take funding out of Singapore overnight, it would be the death of the art scene, precisely because artists rely so heavily on it. The major difference between the region is of course that living in Singapore is much more expensive. And yet, I reflect, at the time of the Artist’s Village there was a very different ethos artists were working by – and funding was not nearly at the level that it is today. And of course when the temptation of the funding is there, it would be difficult to turn your back to it. Jason tells me that Grey Projects, which has been around for eight years, did not receive any funding for first three years. The later three had funding, and now they have no funding again. I asked if they had to adjust the program at the time they receive funding. “We received the funding so we could be in this space long-term. I wanted to establish a long-running residency exchange program. And also to publish regularly. And then I got off the funding so I could do a queer show this year.”

“I guess it’s also about giving yourself the time,” I reflect. “And that is another thing that I think is important to consider. The fact that you don’t have to get to everything at the same time… sometimes you have to accept some compromises. You can see it that way or another way, but then YOU get to have this long-term perspective.”

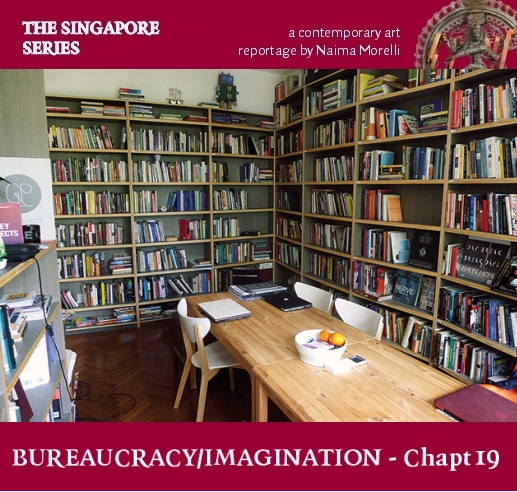

“Correct,” said Jason. “And my goal is always to think in the long-term,” replies Jason. “I want a space where it is not only about the visual arts. It is about creating space… and also from my own interest. It is a space where image makers and artists have a library, an opening, a time for accidental encounters where they can meet and talk with writers, curators. So I’m really interested in image and text. I want a space that supports both.”

Institution vs. independent space

In most countries which have a structured art system, two different circuits are usually represented by the institution and the independent spaces. In that scenario, the market is a third way. In established systems like the Italian one, the independent and the institutional worlds seldom cross. Conversely, in places with a fresher art trajectory like Australia, these two worlds are often in communication, however indirect. You might see someone from ACCA, the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, strolling around in artist-run spaces. Another case is that of places where the institution is almost non-existent, like the aforementioned Indonesia. Here, the independent spaces like Cemeti in Jogjakarta take the place of the institution.

We already pointed out how in Singapore independent art centres such as the Substation have become crucial throughout the years, but there is currently a lack of a network of small independent scenes, constituted by artist-run spaces. As the experience of The Artist Village showed, these are key to creating an independent-minded, original art community.

Jason Wee worked around the idea of an art community even before the actual foundation of Grey Projects. This derives from the way he learned about art himself, namely through artists’ initiatives. He used to hang out a bit at Plastic Kinetic Worms which back then had around twelve to twenty members. The founders were Vincent Leow, Mlenk Pavlialik and his daughter Hanna Pavliaki. “That was an important space for me,” he said with a bit of a nostalgic tone. When Jason was just starting out in the art scene, there were a few other independent spaces including the curatorial collective called P10, which later became the Post Museum, and an artist-run space called Your Mother Gallery, which is still around but hardly programs. “These were the spaces where I could go and meet artists and talk with artists, without having the institution involved.” When he came back to Singapore from New York, this was the kind of community he wanted to return to. “When Plastik Kinetic Worms closed, I really felt like I missed it and I was encouraged by a few friends to start my own space. So I still think it is necessary now.”