THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 16

Take a guess: what is the opposite of artwork? It is paperwork. Whereas the artwork is open-ended, a spreadsheet is self-contained. In other words, the artwork is an object that dispels the notion of identity of objects; a notion which nonetheless is so useful for us to go around the world. We think about a bottle based on its function of containing and pouring liquid. But try to go to Swanston Street, Melbourne on Saturday night, and you’ll see how that a bottle can become a dangerous weapon. For the same reason, we are always very careful to not let kids pick up objects that are potentially dangerous, because children are oblivious to the categories that us adults create for objects and things.

While living outside the categories in everyday life is potentially dangerous – you’d be called a crazy person – the blurring and crossing over of categories is what allows creativity and imagination to happen. Kids are imaginative because they are ultimately approaching things as they are. Infinite. The truth is that things do offer themselves to ambiguity. Contemporary art is particularly apt to prove that.

While ambiguity is inherent in all objects within our reality, we have countless examples of artists that emphasize that notion in their work. To remain in contemporary Southeast Asia, think about Indonesian artist Wiyoga Muhardanto, whose entire process consists of combining two contrasting meanings – for example merging an Apple computer design to an old typewriter, or fusing a fashionable bag with old saggy skin – thus opening up multiple interpretations for the object. We have of course other examples in the milestones of art history, such as Duchamps’ upside-down urinal or Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”. Not by chance, Magritte was part of the surrealist movement, which was all about playing around with objects, subverting their meaning. Surrealists were also very keen on studying dreams – that door to our psyche where things happen outside of logic and the rational realm. In that world, the categories crumble. Our way of thinking about things by free association becomes the reality that happens before our eyes, which is a form of truth – as often madness is.

As we mentioned earlier, for reason of practicality, in our everyday life we think about objects in one single perspective: that of their function. While we ignore this in our mundane existence, we are of course aware that things indeed just are, beyond the function we give to them. While we can’t go around in society in any other way, we must know that we can’t bring this unilateral perspective to everything, on every level of our existence. We can’t for example think about life, emotion such as love or rage, in terms of function – though it is possible. We might know we are in love with someone and rationally is best to us not to be; we perhaps rationally know what is that a certain person triggers in our psyche. While awareness and knowledge always help, those alone won’t necessarily help solve the problem.

We live in a time in history where the scientific method and rationalism are prevailing. This is just a feature of our times, not unlike religion and morality were the coordinates with which the majority of people couldn’t help but think about reality in the past. Today most people are like Saint Thomas; they need to have things proven according to the scientific method – or by an institution representing scientific authority – before they believe they exist. And by all means, this is the approach to go to if we are talking of certain subjects such as health, or say, transportation. But before letting the rational approach be the one and only lens on our reality, we must be aware that science is only a model. It is a model that works, so we shall keep using it until it works for us. So did the typewriter. But we don’t ever have to delude ourselves thinking we have all the answers. We are still largely navigating in the unknown – most of us with the illusion of having most of the pieces sorted out. In truth, we can’t help assembling the little we collectively know and see how it goes.

When I think about knowledge, I think about the cartoon ‘Where in the world is Carmen Sandiego’, an American half-hour children’s television cartoon featuring a charming, red-clad gentlewoman thief. In the first episode, the thief stole Van Gogh’s painting’s eyes and Picasso’s nose and the two teenage detectives deduced that they would steal a famous mouth. So… Monalisa! While this guessing and stretching of the mind to find connections and build model is what us humans must strive for, often times it is not so direct. The principles are easy, but their combination is complex. In that we must humble and know that we don’t know, as Socrates put it, and hopefully give up any anxiety for complete control.

Back to the function of objects. We should narrow our scope to make it more practical and a bit less metaphysical. Art is precisely what reminds us that objects are ambiguous, and that an artwork ask us to open up our imagination and not be taken for the usual meaning we attach to them. When we look at a figurative painting, we see, say, an old woman with sad eyes, not really an overlapping of oil and acrylic. Art is also the un-practical useless human activity by definition. It doesn’t do much directly by itself – or better, doesn’t serve one single clear function to anyone. It is no longer a purview of traditional and religious ceremonies. And since the Renaissance, it is not about beauty anymore. When photography came along, it didn’t even need to represent reality any longer. Together with rationalism, this is a time in history where we can’t escape personalisation. The only thing we can say today it is that it serves personal expression. But then you must justify in the eyes of an art system why, say, therapeutic art made in a psychiatric centre is not of a higher value than one of Maurizio Cattelan’s installations or a Nyoman Masriadi’s painting. There is clearly a collision of factors, and each art system validates art according to different criteria.

To simplify, you can consider art – as any other object – through two broad categories. Their origins or their function (or destination). When we talk about Spirit, like we did in the past chapter with The Artist Village, we are considering art for its function. When we are talking about Market, we are considering art by its function or destination. Again, categories. Keep in mind that throughout this book when I use these terms, I use them as I would pick a colour from the chromatic palette in Photoshop. You must select two colours, in order to start making shapes and start your composition. At the same time, a red you select clicking on a particular point with your mouse is surrounded by all gradients, slowly melting into orange and then yellow, or going purple and then blue. There is no sharp separation, but when you colour your drawing, you juxtapose colours for contrast and to make forms emerge.

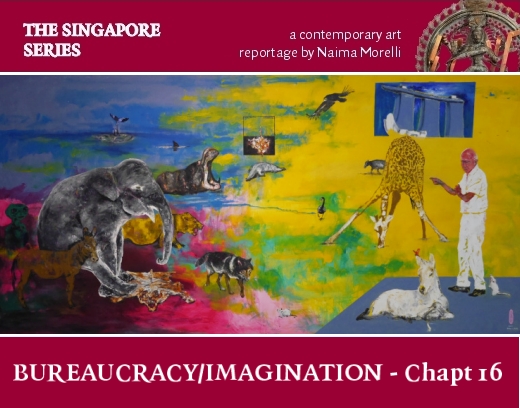

So, Singapore thinks about its art in terms of its destination. It has a goal for it, it is interested in meeting a target. So the system Singapore builds around the arts is one that doesn’t allow the fluidity of art to break the levees. Singapore is precisely where an artwork and its contrasting concept – paperwork – meet. It is the battlefield where the contemporary struggle of bureaucracy versus imagination is fought.

In dialogue with David Graeber

To talk about this battle, I must refer to the work of anthropologist David Graeber, who in 2015 wrote the book “The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy”. The author considers that we are living today in the era of “total bureaucratisation”, where paperwork permeates every part of our lives, in a way unprecedented in history.

It must have been in the spirit of the times, because curiously the same book ended up being central to the curatorial concept of the Taipei Biennale 2016. “Bureaucracy has become the water in which we swim,” told Corinne Diserens, the curator of the Biennale , “We may no longer like to think about bureaucracy, yet it informs every aspect of our existence.” I asked her if she saw bureaucracy permeating the art world as well, and she answered: “The so-called ‘art world’ is not a ‘world’ outside of social, political, economic, and institutional contexts and realities.” Diserens also pointed out that the questions explored by David Graeber which were more interesting to her were two: how to formulate a coherent critique of institutional bureaucracy so that radical thought does not lose its vital center, and how to neutralise the bureaucratic apparatus and the structural violence it produces, the machinery of alienation, the instruments through which the human imagination is smashed and shattered.

Let’s back up a little bit: Graeber talks about bureaucracy as an entity guided by rationality – aka the scientific method paired with the principle of non-contradiction. Seeing as rationality is about the function in terms of technique, the technique creates a working system called ethics, but this is only subdued to the function. Therefore, bureaucracy operates within a value-free ethics framework. It is not by chance that the administrative infrastructure started to come into shape in the 18th and 19th Europe, the time of positivism where rationality was seen as the predominant principle of governance. Curiously, this is the time when most of our favourite fantasy novels such as The Lord of the Rings or The Chronicles of Narnia, often set in a medieval scenario, started to appear (today we have Game of Thrones). To Graeber, this idea of heroism – I’d call it romanticism – counterbalances the dry, bureaucratic reality we are faced with every day.

The idea of heroism in a modern, administrative context is what the late David Foster Wallace tackled in his unfinished novel “The Pale King”. In one moving excerpt, he describes how the protagonist should give up his childhood dreams of epic battles and chances to show his courage through epic deeds in order to become an accountant. Such romanticism doesn’t exist in modern life, let alone in the accountant’s life. The heroism in this scenario consists of enduring boredom every day. That passage reminded me of a reportage I did a few years ago about emerging artists in Melbourne. Though Australia is not as bureucraticised as Singapore, to have access to grants and institutional exhibiting opportunities artists have the chance to apply. I’d then interview artists allocating a big chunk of time to paperwork, trying to get grants or applying for residencies – something almost unheard of in Italy, where the national opportunities are greatly reduced, let alone in Indonesia, where I did my previous reportage, where the government does very little for the contemporary art scene. To the Melbourne artists, it was a career in the arts, certainly not the bohemia they were thinking about when they were reading of Picasso and Modigliani in Paris. Reality check, we might say.

In Graeber’s view, in governance the role of politics is to provide this heroism, a story for the people to follow. Heroic societies are social orders designed to generate stories and in politics rumours, official accounts and made-up narratives are all part of the story and have an impact on how a government gets managed. The anthropologist sees these epic societies ruled by what he calls “egomaniacs” as a counterpart to stable, organised bureaucratic societies.

Teng Jee Hum’s Lee Kuan Yew series

If we think about Singapore with this framework in mind, we are presented with an emblematic example. The nation was indeed built under what many Singaporeans would agree to call the “heroic” figure of Lee Kuan Yew, who, like many larger-than-life political figures, set up bureaucratic apparatus to let his vision run even when he won’t be there. When Lee Kuan Yew died in March 2015 – coincidentally during the 50th anniversary of Singapore being branded SG50 – there was an outpouring of tributes from Singaporean artists. While in the West, artists in contemporary times always assume a critical position against whatever politician is in power, in Asia we see a different mindset. Harper’s Bazaar Art Singapore dedicated an entire issue to the political leader, featuring original work by a number of contemporary artist, along with their thoughts on LKY.

Painter David Chan represented Lee Kuan Yew caressing a Lion: “Mr. Lee struck me as regal, yet pragmatic, stern yet caring. I hope Mr Lee will be remembered as a watchful guardian who groomed the uninvited lion into a noble beast.” Adeleine Daysor realised a fabric patch with Lee riding a bike with the writing “Did me good”. She said to Harper’s Bazaar: “In the book Hard Truths, Lee Kuan Yew advocated cycling, saying it kept him fit. In art history, great leaders are also portrayed on their mounts to indicate their mobility, outreach and capacity. So this image of LKY on this humble bike is very heartening for me.” What was also telling was a photograph by John Clang called ‘One Minute Silence’, a self-portrait with his parents, wearing a Chinese funeral mourning outfit, which is specifically meant for the son to wear while mourning for his deceased parents. “It’s the utmost tribute I can offer our founder, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, as I am wearing the mourning outfit while my parents are still alive.” All these representations in the aftermath of LKY death were straightforward celebrations. Throughout the years, artists sporadically tackled the figure of the political leader leaving room to shades – think about works such as ‘No More Tears Mr. Lee’ by Jason Wee, part of the permanent collection of the Singapore Art Museum. However, one artist who consistently dedicated a big chunk of his ouvre to this larger-than-life figure, highlighting its problematics aspects as well as the heroic one, is Teng Jee Hum. From 2010 to 2015, he realised a series of paintings – collected in the book/catalogue ‘Godsmacked’.

I met Mr. Teng under the guise of collector rather than artist. He is a fascinating person who really cares about contemporary art in Singapore, and he isn’t afraid to break boundaries, participating in it in many different roles. One day he lent me a book of his painting works, plus a few texts by him, which we could define as the subject of Singaporeaness. As I opened the book and read the introductory text, it hit me with its straightforwardness. It was like all the appearances which for understandable reasons, Singaporean artists keep up, were suddenly uncovered. Without anger, or rage, or resentment, or provocation or pushing a political agenda of rebellion. Only with a sharp sense of awareness and acknowledgment of the good and the bad in that huge data that represents what it means to be Singaporean. The exceptionality of being Singaporean is seldom acknowledged, especially in the art world. All the time I see people who are just passing by the city port, preferring to head to other cultural centres of Southeast Asia, be it Yogyakarta, Chiang Mai or Saigon. Singapore is not so in-your-face interesting. It is that introverted guy that you need to spend time with to have it reveal its true nature.

To Mr. Teng, the title of the book ‘Godsmacked’, represented the sensation Singaporeans feel when realizing that their life has been completely modeled after the dream of one. It is a “wake up Neo” moment. Here I must quote part of the text:

“Once, in the 1970s, it was deemed to be getting crowded on this little island, due to its limited resources. Now we are told there aren’t enough of us to produce GDP. The cleanliness of the air I breathe, the kind of water I drink and wash in, my modes of getting around, the thoughts I think, and many of my other daily habits and actions (well, mostly reactions) – have been specially moulded, fashioned, conditioned, calibrated and recalibrated… as part of an obtuse grand scheme of things. As it dawns to me, I realise I am a product of another’s deliberations. This is who I am – a Singaporean”

“One’s cultural mores, world-view and attitude towards life are, I suppose, normally inherited from eons of social evolution, but here I seem to have mine downloaded from a central intelligence. Countless campaigns over decades wrought changes to my mindset and reset my social behavior. Singapore became an efficient economic machine, world beater and number one in many spheres and measures, the foremost of which is per capita GNP. Such an achievement justifies recognition as to how Singaporeans collectively come by it – and we are in unanimous agreement that there is one single factor that outweighs all others combined. This one is Leadership, or shall we say, the leader – functionally also the “founding father”, programmer, mega-thinker and strategist, also a social engineer, hero and creator.”

The body of Mr. Teng’s work in the book is divided in two parts. The first is named “Singular Phenomenon”, and the second is called “Singular Plurality”. In the first part, the artist looks at LKY as this figure who came to represent so much for all Singaporeans. As all father-like figures (“my father, my mother, my leader, my employer, my benefactor… ad infinitum”, Teng says in the book), the artist has a complex relationship with him. Strong of a background which we can really call postmodern – mixing references from politics, Chinese traditions and American comic books, the artist comes to identify the leader with Superman, Confucius, Cai Shen Ye, Bruce Lee, Wu Song, Moses and The Silver Surfer. Both titles put emphasis on the “singular” element, on LKY as a creator shaping reality according to his own singular vision – something common to all great political figures and, as curator Seng Yu Jin points out in the book, to superheroes and supervillains in comic books who try to shape reality according to their superpowers.

Every utopia is someone else’s dystopia. After all, every kitchen-table debater likes to talk about their ideal society and country. The thing with Lee Kuan Yew is that he succeeded in making it real. In the introductory essay, Teng Jee Hum describes the three nationality changes he went through (first a colonized British subject, then a citizen of a merged Malaysia, and finally a citizen of newly-independent Singapore), along with a complex entanglement of all the languages he had to learn in school and his Chinese heritage.

In the second part, he analyses the effects of this social engineering experiment. In the book there is a quote from Einstein saying that concepts which have proved useful for ordering things easily assume so great an authority over us, that we forget their terrestrial origin and accept them as unalterable facts. “The influence of one man has been so great as to be almost, paradoxically, invisible to common Singaporeans – the way water is invisible to a fish. A yet, the fish cannot do without water. When I look around, I find most Singaporeans are like me, fishes in the same sea.” This is the case with bureaucracy in Singapore, and the man who highhandedly started it.