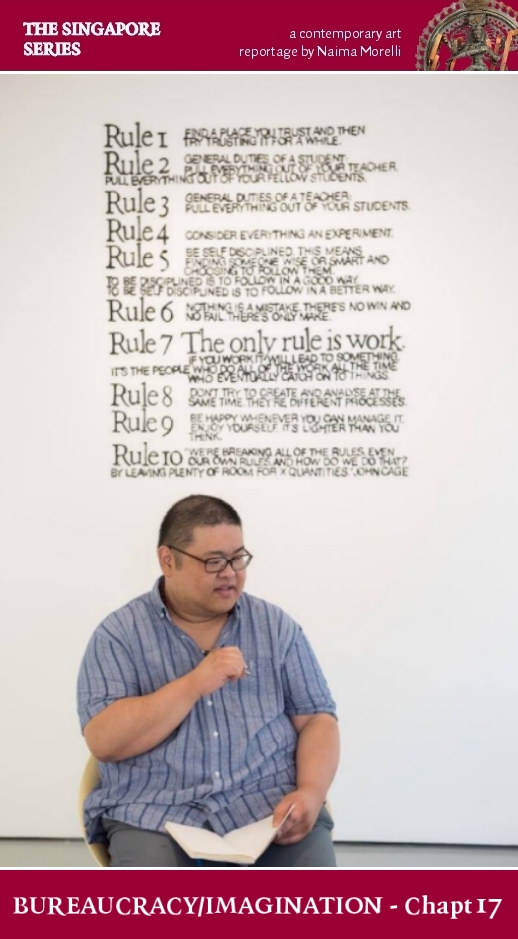

Lim Tzay-Chuen’s elliptical approach

It’s a matter of fact that when a concept is so deeply embedded in a society, often artists tackle it not as a separate topic, but in its many manifestations. As Tan Boon Hui Calvin, Vice President, Global Arts & Cultural Programs and Director, Asia Society Museum, NY, à Asia Society, puts it : “The best work engaging with the concept of bureaucracy is the elliptical in approach. I honestly do not think it will be as blunt as ‘bureaucracy’.” One example of this elliptical approach is the work of Lim Tzay Chuen.

The artist describes his work as being concerned with “offering” solutions to possible problems, becoming about administration and organisation – aspects that are an integral part of the art world, but are usually left out from the official narrative. For the Biennale of Sydney, he designed and coordinated an open proposition to the public: “Enterprising” persons who got hold of certain pages from the 2004 Biennale catalogues would enjoy the privilege of using the Artspace Gallery 1, AUD $4000, 4 nights of hotel accommodation and official inclusion as one of the invited “artists” to the Biennale.

Read More