THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 21

Gerald Leow

“Why should the government pay you to have fun?”

Yeah, right, why? Gerald Leow was the first person who phrased the question in this way. It shows that the kind of questions you ask, and the way you ask it, can result in overturning an entire vision, or perhaps making some hidden dynamics come to the surface.

This very simple question is one which artists from other countries would have asked themselves visiting Singapore, but a question that perhaps not many Singaporeans are asking themselves, perhaps not in this way. Gerald is aware of it: “I have very controversial views. I think as an artist…”, he hesitates as he ponders the words. “That’s the only thing that makes you special. It’s your mojo, you know? And then instead of protecting this thing and having full autonomy over it, you give it to someone else and say, “Here: how about you dictate what kind of work should I do?” To me it sounds ridiculous.”

“You can give a billion dollars to the arts. You are not going to produce John Lennon.” I asked if in his opinion, the funding is damaging the arts in a way. “It’s not damaging, it’s just two different agendas. The people who fund it have their own agenda the artists do art have their own agenda. And the two shouldn’t meet. The funding for the arts, and I’m saying in a bigger picture, not specifically Singapore, funding for the arts it’s really a government big picture planning kind of agenda. The artist is one guy, what you do, what you draw, Snoopy or Garfield or whatever, it’s you. It shouldn’t cross. However of course, they can happen to overlap at times.”

“I want to run my own show. I don’t want someone telling me what to do. And really the difference is whether the work is this big or this big. You know what I mean? I can make a ring in the same spirit of Judas Priest. I can make a sculpture. I can play a gig at home in my bedroom, with nobody listening, just you and myself. It’s still a concert. For myself. I can play at the Royal Albert hall. It’s just the skill. The work still exists. It doesn’t diminish the importance of the work. Or the spirit of an artist. This is just my personal view.”

I got a good feeling about Gerald Leow since seeing his work for the first time. The first time I encountered the artist’s work was at the exhibition on Southeast Asia at the Palais de Tokyo. He presented a traditional hut shape according to some forms modelled after metal fonts. I later learned that he wasn’t concerned with being presented as a Singaporean artist: “It’s not problematic to me. They can say what they want to say. You go crazy if you listen to them.”

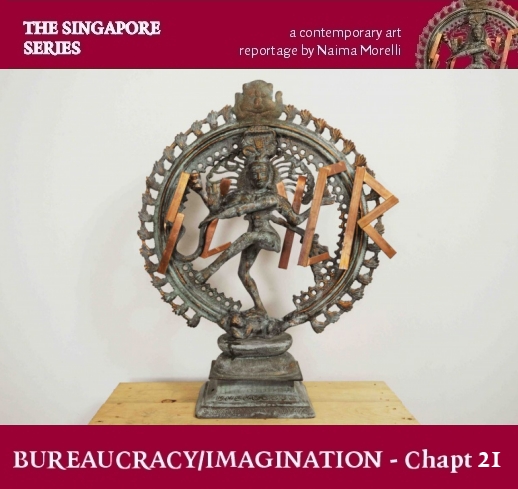

But perhaps the very first time was in the room of the National Library in Rome, where somehow I managed to get my hands on the “Singapore Eye” catalogue. Browsing through the pages, letting the images sink in before reading the artists’ bios and their description, I abruptly stopped at a page where a gigantic font sculpture called me due to its familiarity. A puppet was squeezed under the letter A of an Anthrax logo installation. Anthrax, the heavy metal band. But what attracted me the most was a traditional statuette of Shiva dancing on the background of a Slayer logo. Yes, Slayer, the heavy metal band. The same power, the same strength, the same lyricism, the same mysterious, generating and destructive force was conveyed both by the artefact and what it symbolises, and the echoes of that powerful music in my ears.

Connecting something very old and mysterious to something very new and apparently mundane is like casting a spell. This spell somehow clears up our thinking in rigid categories and reveals an underlying reality where everything is connected. The objects invested with this spell are the works that the artist creates. You can put it on your shelves, and every time you look at them, you are drawn into the ambiguity of reality.

“That’s such a sacrilegious work,” is what Gerald told me when interrogated about the Shiva work. “Such a bastard work. I feel the Singapore art scene perceives me as a bastard as well, a bit between here and there. Like I’m not a sculptor, I’m not somewhere in the middle. Stage designer is my day job. I do a lot of projects, like I’m designing the costumes.”

“Actually people think the Shiva is a sacrilegious work, but it’s not. Shiva is the destroyer, so it’s so funny we have the same concepts in two different cultures. But I changed the font and then it becomes something evil. But these concepts are not in Hinduism you know. The idea of Slayer, the band, this idea of good and evil is a very Christian concept. The concept of the devil. But in this you can’t draw parallels with Shiva the destroyer. It’s two different universes. This kind of universe produces a certain object and artefact. So this is Shiva. Modern cultures produced Slayer, and it’s the same thing. But you can compare them and put them together. For example, in your thunder earring, I see Judas Priest. But you can talk about it as a sculpture, and an earring. It’s how we choose to talk about it. And that’s the spirit of good art. I guess. You put it in a glass case, or in a museum, or you hang it in this run down hawker centre, same spirit.

We had this conversation at the table of a Singaporean hawker centre. The artist was a laidback, reserved and frank guy. He didn’t even have the chance to speak, before I told him barely containing my enthusiasm: “You know, I don’t usually say that to artists that I interview, but your work is awesome!”

He thanked me, perhaps hiding his perplexity about this total fangirl, and complimented my thunder-shaped earring. Gerald Leow has an anthropological interest in art. He developed an early interest in art as part of his childhood, as any child goes to school and draws. “You find you’re good at it and you enjoy it but it was never an option to consider because I come from a family… most Asian families really, it’s not something that’s done.”

His training in art came from a hands-on job he had, training as an apprentice making props for an Australian man, which was his boss. Then they became good friends, and then partners in business: “I learned everything on the job, how to carve, that was my education.”

He then proceeded to study sociology, which ties in: “I’m addicted to learning. For me there is no difference between learning theory and learning with my hands. In social science there is theory, but there is also field work. Two sides. So when you look at an object, it’s the same, you have this object with certain properties. Is it hard,? Is it soft? So here there is theory involved as well. I did three years in social science, didn’t get very far. It was very theory-based and collecting data fieldwork was very simple. But they gave you a very good tool box, the way of thinking and understanding concepts, it helped in understanding art theories. Karl Marx, to postmodernism.”

Postmodernism I guess was a big thing for you, mixing high-brow and low-brow in your art. How old are you?

Thirty-one. In our generation, there is no respect for anything! It’s easy especially for people in Asia because we don’t have a classical tradition. We never have. I never had any teacher, never went to an academy, especially me because I never went to art school, everything is free to use, we have no baggage. I mean there is baggage, but I used it to my advantage as part of my language. There is no kind of reverence I guess.

That is definitely something central in contemporary art, but coming to Asia I’m always surprised about how this distinction is never felt at all, whereas in Italy there is always a reverence in the way you study it and see it every day.

Art school also frames your mind. Not going to art school, I always took in low-brow as art as well. And then you end up looking at… heavy metal.

Tell me a bit about your interest in metal!

I think it’s visual culture.

Okay, so you look at it as visual culture, it’s not that you’re a fan…

No, I’m not a fan.

Whaaat? You’re not a fan?! I was so anticipating discussing with you the latest Judas Priest album!

I know my material, but I’m not a fan. I’m not a metal-head.

So what music do you listen to?

Everything. Everything.

So why do you focus on heavy metal?

Metal’s so interesting because there are so many signs and so many symbols in it. There’s a lot about power. And it’s so stylised. And I use it as a symbol of colonialism actually. So it’s very much about power and metal as material is… heavy, you know.

Can you go into a little more detail about metal being related to colonialism?

Because my interest is the story that the object has to tell. So metal is an object, right? Culture is an object, it has certain properties. So this object I think is produced by a certain culture. If you look at Japanese paintings, a certain culture produced flat paintings that are flat, you know. So if you want to understand a culture, you can understand it from an object. So heavy metal is an object. So the ideas behind it, even the myths and the story behind it, like Judas.

“After the mosh pit I was left with Judas”, can you tell me a bit about this particular work?

Oh yeah. No one likes that work, but I love it. I always wanted to develop it more, but I never had the chance. For that project, I just saw that Judas were coming and I just bought the tickets. Really expensive. So I went to the concert, I was with my ex-girlfriend and I said, “okay, you take pictures for me.” So the whole idea for the artwork came from just an idea that I had, how I wanted to compare Judas Priest with another culture, a traditional culture. At the time, I was in Bali a had a business there. So I find it so interesting to compare these two cultures. On one side, you have Judas priests in the mosh pit, and on the other side you have the Balinese dance. The Barong dance. From here, in Judas you have the Priest on stage and for this you have the Witch Queen on stage. And here you have mosh pit, here you have the people in a trance, in the traditional dance, stabbing themselves with the Kris. You have the smoke machine, you have the incense. It’s the same thing. They are both an idea of a ritual and a trance, ecstasy. So I took a video actually of them in the mosh pit and security were carrying people away and in the Balinese dance, they were in trance and people were carrying them out of the trance. And the people walking out of the stadium and the people cleaning up the temple after the ritual.

So it’s the same dynamic in a different time with a different aesthetics.

That’s the essence of it. I feel like the nature of Singapore is like Judas, nobody’s child. Not yet Asia, not West, I was educated in western concepts, western kind of rationality. We are biting the hand that fed us. We are kind of a Judas you know, like a bastard child.

I really like this comparative attitude in your work. Actually the reason I like your work so much is because I was…

… a heavy metal fan.

Aside from being a heavy metal fan… I’m more into punk really, but I obviously appreciate metal.

Actually I have to say I used to listen more to punk!

Good, what were you listening to?

Everything! But more skate punk because of my generation, Nofx, that kind of thing. And of course you have Heavy Metal and Hardcore and everything else. I got the Mohawk and I was really into that.

When I ask him about his projects, he explained to me that he does only one painting a year. “I have a job,” he said matter-of-factly, “so I’m slow.”

I noted that this was probably good, so he could avoid overproducing and getting stuff out which is not necessarily desirable. “Yeah, overproducing is shit. It just means that the work is not good enough so that you can’t distillate into one.”

I hint to the market need of having artists presenting new work, and the requests of galleries that pressure the artists. Gerald replies with his usual quiet sharpness: “Then they should hire a PR agent to represent them. Like Katy Perry or Beyoncè, look at yourself man, fuck you, you’re not Katy Perry! My good friend Kai in Paris was asking me about the art scene and I told him that an artist shouldn’t think about these things! At the end of the day, people are betting horses. You don’t ask the race horse if he can win, the horse just runs. That’s what we are, we are horses. We only know how to run.

Yes, but at the same time I think one must be aware of their surroundings.

Yes, but that’s in the field of what we can run. That’s how I see it. Even someone as glossy as Jeff Koons, he has the will and the want to create and that’s the purity of it. Whatever you own is your dress, but the instinct of running is there. The existence of that is what’s more important. The rest are add-ons. Some people want to put importance on the rest. It’s fine, to each their own, I think. But I don’t see myself as a professional or a successful-whatever-that-is.

I really like your take on that. It is not common to be so outspoken.

I have controversial views. I think artists should have day jobs. So people can’t tell you what to do. It’s not uncommon. I read an interview with Francis Ford Coppola where he said, “if you have a day job, you wake up at 5 am and you write the script, that’s the way it is.” It’s just a different model. In the end, it’s a business model of sustenance, because you still have to pay rent, eat, buy clothes. So the different models, many roads to Rome. So often people talk about one model of being an artist, which is either funding… or the idea that the artists have to have a studio.

It’s just the artist subscribing to the idea of what an artist should be.

If you look at outsider art, that’s why it’s so exciting. One of my favourites is Henry Darger. He was a genitor, they thought he was a bit low IQ and when he died, they had to clean up his house and they found thousands of manuscripts. Drawings. And he created a whole universe of characters, little girls, they were called the Vivian Girls. He created a universe of writing and beautiful drawings. And the girls all have penises. Because he didn’t have any idea of female sexuality, because he lived alone and he was an orphan. So he produced this huge body of work. Of course now he’s really well known, but he died without anyone knowing about his work. The work exists, whether anyone sees it or not.

That is true. At the same time, there is this sadness if a work is not shared.

That’s the main difference between Henry Darger and us living in the internet world. The idea is that as an artist you have to consider your audience, whereas Henry Darger doesn’t consider an audience. So it’s not on the same level, you’re not producing on the same level.

Speaking of audiences and how the anticipation of their reaction can push artists to adjust their work, we should speak about censorship. As I understand it, here that’s a big thing…

I don’t know, I don’t understand why it’s a big thing. It’s the discourse of Singapore. You’re so savvy now, why does nobody censor porn on internet or… it’s stupid. We have so many ways to share information today. It’s so difficult to censor information, so how can you still talk about censorship? The thing they censor you for… of course they pay your bills. They pay your salary. The boss is not going to pay you if you’re like “hey fuck you, I’m not coming to work tomorrow.” They’d say “don’t talk to me like that, I’m paying your salary”. Everywhere in the world, it happens in liberal societies. It happens in very young nations like Singapore, it happened in primitive societies six thousand years ago. I think the discourse is framed. You can’t solve the problem when you still look at it. It you frame it as censorship, it is censorship. If you think you smell shit, you smell shit, you know what I mean? Okay, this is from a social science point of view. I have an idea. It’s a very simple idea. The result of the study that you get is determined by the data that you choose. I have a theory that people with black hair are stupid. So you frame it like that and you look for people with black hair. You start from there, it’s how you classify people I guess.

Yes, it is about categories. About the specific knife you use and the way you decide to cut your perceived reality with it. For the Singaporean art scene, it’s impossible to have anything but a partial vision.

There shouldn’t be one point of view. When there is, it is problematic. When someone says, “look, I have the definitive guide. Just follow my guide and you get the real stuff. Every time it happens, it’s bullshit. It’s like state media. They try to tell you this is the truth. So you always have to find a second opinion. The West sees Singapore being all about censorship. Because you have liberal media and you have conservative media in Singapore.

You started from painting and I see that you evolved in a way, starting to increasingly working at the space.

Actually no. It’s all about opportunities. Because some good people believed in me and gave me the chance to do large works. Now I don’t have a studio anymore, I moved back to a small house so I don’t have space, but that doesn’t mean you can’t do large work. It’s all about opportunities.

Aside from the opportunity factor, has your way of thinking about the work changed over time?

Although the way I do the work hasn’t changed, the way I think about the work has changed. When I was just starting out, I thought being an artist was being an individual and making your voice be heard. Me, my ideas, my voice, my opinion. But two years back I started thinking it’s the exact opposite. It’s never about the individual, but always about issues. Great art should be about things that are bigger than ourselves. It’s about love, it’s about betrayal, hate, sadness, war, you know… and we always say, “oh he’s a great artist, in the way he sees they world”, but no, it’s how love, hate, emotions move him, and it’s always about the emotions, the humanity. Even if the artist didn’t exist, someone else world make the work.

In every artist is their own personal, different process though.

In a different way.

What’s the need that pushes you to make art and the role that art has played throughout your life?

It’s just another way of thinking. I’m very curious. I’m interested in a lot of things. Not being good at it, but I’m interested.

What is the Genesis of Brave New World?

So there is Iron Maiden of course, and Huxley. So Iron Maiden commissioned a digital artist to make the album cover: It’s a futuristic London. That work is fucking cool. (Laughs) So I did the painting, it took me one fucking year to do the painting. Have you read Huxley’s book? It describes a dystopian future. So over the painting there is a video of modern Singapore which looks like future London. The video changes perspective, so at one point the worlds line up and the painting looks like it’s moving, you know, and then there is a dramatic ending because the city goes below. It’s really nice to see the work in person, even if didn’t get the chance to see the work before installing it, because my studio is so small and I don’t have a projector, so I borrowed one from my housemate Lee Wen — I used to live with Lee Wen — and so when I finally saw the work I thought, “woo, that’s quite cool.” I had never seen it before I had the chance to exhibit, but I still did the painting.

Not having the chance to see how the work would look before exhibiting, how did the practical side and the conceptual side work together?

They are tied because the practical side is about opportunity cost, you lose money, you lose time, you have the concept, it might not work but it’s an experiment. I created pieces that I worked on for a few years and just ended up in a dead end. I spent thousands of dollars and they never saw the light of the day. I made one when I was in Bali. I had a lot of money at that time because of the business. I was doing a stone carving piece and commissioned stone carvers in the village to do an Iron Maiden CD cover in stone. It was Ivan the great. I never showed it, I discarded it. I didn’t have the chance to show it and when I moved out of the studio, I didn’t have the money to keep the thing. It was cheaper for me to throw it away. I don’t even have a picture of it, but when I brought it to Singapore it was all in crates, all in pieces, I never assembled it in Singapore ’cause it’s site-specific. Too bad, you win some you lose some. Okay, I’m so hungry, do you want something? I’m starving.