THE SINGAPORE SERIES — CHAPTER 17

Lim Tzay-Chuen’s elliptical approach

It’s a matter of fact that when a concept is so deeply embedded in a society, often artists tackle it not as a separate topic, but in its many manifestations. As Tan Boon Hui Calvin, Vice President, Global Arts & Cultural Programs and Director, Asia Society Museum, NY, à Asia Society, puts it : “The best work engaging with the concept of bureaucracy is the elliptical in approach. I honestly do not think it will be as blunt as ‘bureaucracy’.” One example of this elliptical approach is the work of Lim Tzay Chuen.

The artist describes his work as being concerned with “offering” solutions to possible problems, becoming about administration and organisation – aspects that are an integral part of the art world, but are usually left out from the official narrative. For the Biennale of Sydney, he designed and coordinated an open proposition to the public: “Enterprising” persons who got hold of certain pages from the 2004 Biennale catalogues would enjoy the privilege of using the Artspace Gallery 1, AUD $4000, 4 nights of hotel accommodation and official inclusion as one of the invited “artists” to the Biennale.

Indeed, a big part of Lim’s conceptual art practice deals with the way art institutions engage with artists and the public. Another example is his work for the Singapore Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale. Lim had originally proposed to uproot the Merlion, national and cultural icon of Singapore, and bring it to Venice for installation in the courtyard of the Singapore Pavilion. However, this plan was considered impractical and too costly by the Singapore government. Instead of getting discouraged, Lim decided to get meta: he produced an installation for the Pavilion and placed outside its entrance a signpost which read: “I wanted to bring Mike over”. The bureaucracy and its hindrances were brought to light.

Jack Tan’s legal aesthetics

As David Foster Wallace put it, the real invulnerability in modern society consists of the ability and resistance in dealing with boredom. This doesn’t mean necessarily giving in to it and becoming boring, but rather finding a way to let imagination leak in. In other words, transforming the self-contained into something open-ended. While Apollo is trying to contain Dyonisus, having Dyonisus embracing Apollo in return.

This approach is something I have found in the work of Jack Tan. At the SAM8Q building, where part of the Singapore Biennale was held, I encountered “Hearings”, a 2016 work by Jack Tan, consisting of bound manuscripts, music stands and speakers with a set of eight audio recordings accompanied by textile.

In Italy, there is a famous virtuoso singer and TV personality from the ‘60s called Mina. Because of her voice, it was said that she would be able to sing anything, even the yellow pages. In a way, that is what Jack Tan did in his work, making the Anglo-Chinese Junior College Alumni Choir sing the hearings from court proceedings. The work was in fact born out of a collaborative project with the Community Justice Centre (CJC), which explored the experience of litigants-in-person at the State and Family Courts of Singapore. As an artist-in-residence at CJC and the Courts, Tan attended, listened to the soundscape of the courts, paid attention to the use of voice and documented what he heard in the form of drawings. The artist turned his drawings into graphic scores, which were then interpreted and sung by the Choir.

Not only in this work, but in his entire practice, the artist brings art and law together to explore what he calls ‘legal aesthetics’, which is also the subject of his PhD at the University of Roehampton, London. Prior to becoming an artist, Tan trained as a litigation lawyer and worked in human rights non-governmental organisations. As an artist, Jack uses social relations and cultural norms as material, creating performances, sculptures, videos and participatory projects that highlight the rules – customs, rituals, habits and theories – that guide human behaviour.

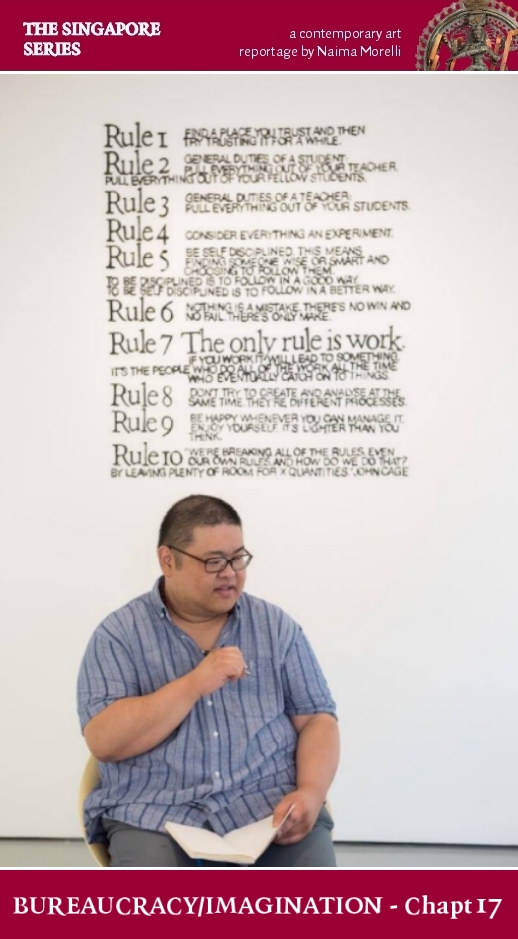

In his 2015 exhibition “How to do things with Rules” at the Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore, Jack Tan examined how rules are socially, emotionally and legally constructed. Using the gallery as a social and exhibition space, Tan presented a series of performances, sculptures, video and participatory works that reimagine social customs and rituals.

In the central encompassing piece “Karaoke Court”, he reproduced a functioning court office, library and meeting areas. He developed a method of legal arbitration with the staff and the students at LASALLE College of the Arts – which the Institute of Contemporary Art is part of – and the local community.

Trained in ceramics, the artist also presented two pieces which incorporated ceramic artefacts. “Decision Pong” was made of a ping-pong ball and a set of ceramic cups, with “decisions” labelled on each one of them. A decision was made by throwing the ball and seeing which cup it landed in. “Hard Copy” consisted of a set of three ceramic sculptures that formed the signed exhibition contract between the ICA (Singapore) and Jack Tan. This was inspired by the ancient Mesopotamian practice of inscribing legal documents into stone or ceramic (kudurru or boundary stones).

Another piece “Conch” can be used to impose a rule of turn-taking during meetings whereby the person holding the conch has the right to speak, while in “Ballot box” he created a tool for taking secret votes during meetings. Instead of the usual metal box, this ballot box takes the form of a tactile burnished ceramic pod.

The work “Visitor Service Officer” highlights the rules and duties of gallery invigilators, and how their behaviour affects visitors. In this work, the artist creatively interprets the official job description of the ICA Singapore’s ‘Visitor Service Officer’, and asks to them to perform various tasks as part of their daily work in the gallery. The interactive performance “Art School Surgery” took the form of a thirty minute life coaching session with the artist about how Sister Corita’s Rules apply (or not) to a person’s professional life. Finally, in the performance “A Kiss is Just a Kiss”, the artist makes empathy and human connection override the dry and cold rule-making, kissing the visitors.

Terry Wee, the reduction of language

In April 2015, Utterly Art Exhibition Space hosted a show called “Panoramic Mastermind” by three young graduating BA(Hons) students from LASALLE College of the Arts called Terry Wee, Hyrol and Asanul Nazryn. The show was based on the idea of the State as a physical and mental space, simultaneously pushing different ideas of drawing processes in their works. Besides occupying a physical environment, the State also encompasses a state of mind which is hidden from casual observation. The artists attempted to illustrate a panoramic view as they compiled their narration of Singapore’s identity by utilising new media techniques to explore different terrains of this utopian state. Nazryn created drawings and videos using sounds to generate landscapes based on National Day speeches. Hyrol’s art was based on his idea of mobility, and how through mobilising his body, non-physical spaces can be manifested in his photography. Terry designed his works based on Microsoft Excel tools. He alluded to the role of an artist today as seemingly becoming a paper-pusher.

In the trio, Terry Wee kept the line of investigating bureaucracy, the reduction of language, self-purification and self-censorship in Singapore and beyond. Indeed, part of his body of work is called “administration”. His recent works aim to reflect the realms of administration and its systems that seemingly dwarves us into self-censorship individuals, striving citizens living in the errors and awkwardly perfect world of today’s administrative culture. In the work “Micro-Landscape” he exhibited a fish tank in which pieces of newspaper were slowly melting in the water. His idea was to represent an isolated dimension to criticise Singapore’s media constraints and strict rules. The water served as a metaphor for the ‘sterilised’ environment in which media must operate.