THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 9

The norm and the individual

My curator friend Roberto D’Onorio and I have very different tastes when it comes to historical figures. I have always been all about the bat shit crazy personalities such as Caligula – which obviously attracted me for their romanticism, their “freedom in their own psychosis”. Conversely, Roberto has always been all about the composed, formal figures, among which his favourite is the Queen Elizabeth II.

He doesn’t just like her. He’s crazy about her to the point that he watched all the documentaries about her, all the series and of course the movie “The Queen”. What he likes about her is that she, unlike her other contemporaries such as Churchill or Margaret Thatcher – who by the way was referred to as having the lips of Marylin Monroe and the eyes of Caligula – was a sane individual in a system which required her to be there.

She didn’t have to make any kind of choice, she just had to follow a protocol which was already laid out for her. She just needed to embody it in the best way possible, and adapt her personality to it. As Roberto pointed out, Elizabeth was a sane individual operating in a system that catered to her. The system itself was something that had no reason to exist other than to keep power structures in place. And that brings us to talk about Singapore and its artists.

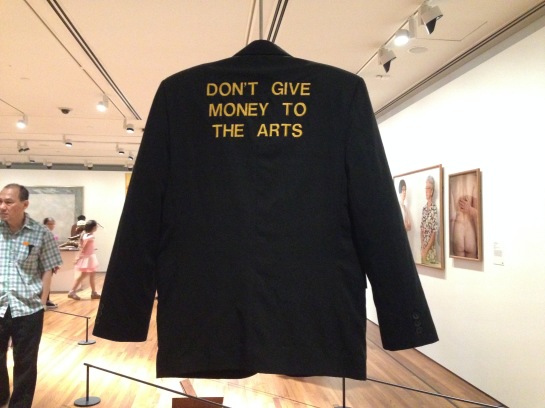

We can pretty safely say that the first generation of Singaporean artists was operating in an adverse environment. This made them somewhat romantic figures, which is of course the way in which we traditionally see artists. It is common knowledge that artists don’t conform to society, but are actually going right against it. They can never be “healthy”, if sanity corresponds to working in a normative system. They couldn’t concentrate just on the art making, because the system was not there, so everything needed to be questioned and build up. Conversely, the young Singaporean artists today are able to follow a sort of protocol. There isn’t too much choice involved compared to their, say, Italian counterparts. The latest wave of artists is born into a system that needs them to produce. There is also in a market, so while they won’t necessarily sell, there is still the possibility of a market. The problem is that the system is there to create a system, so in the higher sense of what art is supposed to be, “It should not exist”. The artists that conform are a bit like the Queen Elizabeth – very good and sane, acting in their role in the best way possible, by getting high education, prices and qualifications in a credentials-based society. Which is somehow what every artist wants deep down, not even admitting it to themselves – not to be romantically alienated from society, performing the theater of pain, but rather being connected and happy. But what they really want is to work in a system that caters to them, but that would also reflect their values, not catering to what the market would like and the productivity indexes. While this dynamic is underlying to the Singaporean art system, artists live through it in a very diversified way. They are neither total conformist or total anti-conformist. Neither naïve or arrivistes. They are humans responding to an environment.

Art as a career

I explored this idea of artists conforming to the norm with Jason Wee, who has quite a thorough perspective, being an artist as well as the founder and director of Grey Projects, one of the couple – at the time I’m writing – independent art spaces in Singapore. He noted that often art is regarded as a career in recent times: “I think the Artist Village for a long time had a number of practitioners who were friends, who really saw art as a way of standing a part from urban development or from the market economy and also from normative ways of living,” he observed. “But I think now especially in Singapore, it is professionalized to the point that they have business cards ready at the hands, and they have an artist statement always at the ready. They expect to get an award at certain times, they expect to be at art fairs. And they are much less inclined to question how culture became an industry. They in fact see this as an opportunity.”

While this is a very strong tendency in Singapore, he cites a few examples of artists which elude this kind of scheme: “There are bunch of artists who don’t have great market success, but they are very respected by artists – most of his work is institutional indeed. Professionalization in art sometimes corresponds to a very strong desire to make things straightforward. To make your entire practice straightforward, so you are an artist who is only about these things. Or you are an artist because of the grant you received, for example. You are only adjusting to these things. So I find myself often very attracted to works that are willing to not be so simple. I’m looking to be moved just like everyone else, looking to be surprised, but I think sometimes the work that really stays with me longest is the work that is not afraid to be difficult or complex. Whether it is an emotional complexity or a kind of complexity or perspective, they are willing to take to poetry, conflicting positions at one.”

Jason feels that in Singapore there is a very strong division between “institutional” artists and “market” artists – those who work for galleries. However, he himself represents an exception, having exhibited both in public and private spaces: “For me it often about this skill of what I want to do and what is the right space to say the right something. So I did a queer show and there is no way I could have done that when I was a very young artist. There was no way I could have done that in a museum, because no museum would support it. And there is no way a gallery would support it because they couldn’t sell it. But I can work with a space with the Substation gallery to do it.” Other times, for him the ratio would have been represented by the fact that he wanted to do a show catering to a wider public: “For me it is not so much about whether I sell or not. It is much more about finding the right space for the right audience.”

Market setting the criteria for art

We have seen how the first generation of Singaporean contemporary artists from the ‘90s felt very distant from the market. At that time indeed, there was no art market at all. As Amanda Heng pointed out though, the society was already money-centred. Today the art market is growing bigger and bigger and this results in price points setting up the criteria and legitimising art as a thing. Coming from Italy, I see a stark contrast. Here the market is never seen as too much of a good thing, being a clear distinction between a “noble” market, which is the one of the galleries, versus the auctions, which are seen as “vulgar”. In the European art world, most of the time artists avoid talking about the market. The artist must be something completely ethereal, with don’t need to eat, pay rent, and even less so go to the toilet. A curator I knew told me that he never told his art critic teacher he was working as a clerk at Zara by day: ”I just can’t. If I told her she would forever write me off as a Zara clerk and refuse to work together in the future.” Even artists like Jeff Koons, who are clearly commercially successful and even play around with the convention of the market, know that for their reputation it’s best to zigzag the question, as Sarah Thorton recounts in her book ‘33 artists in 3 acts’.

Aware of this feature of the art world, fairs like Artissima in Turin are following the Art Basel model, making room for performances and other form of arts which are more appreciated by the critics, in the impossible effort to make people forget they are in a place were objects are sold.

Although as Jason Wee noted, there is a clear distinction between institutional work and market work, in Singapore and Southeast Asia the snobbism towards talking about market it is non-existent. That is shown also in the decision of placing art galleries inside malls. In Singapore, one such sought-after space called is ION, which is a mall just down from Orchard. This presents itself as a 4,000 sq ft of exhibition space to introduce new and multi-media art into the “Integrated Mall experience” and “Offers the best of Asian and Singaporean modern and contemporary art and design from established and emerging artists & designers.” It comprises, along with a couple of private galleries, also lifestyle retailers including restaurants and furniture stores. Which dissipate every hope that contemporary art in a mall would be an experience to favour inclusion and discourage elitism, being designed as a luxury experience.

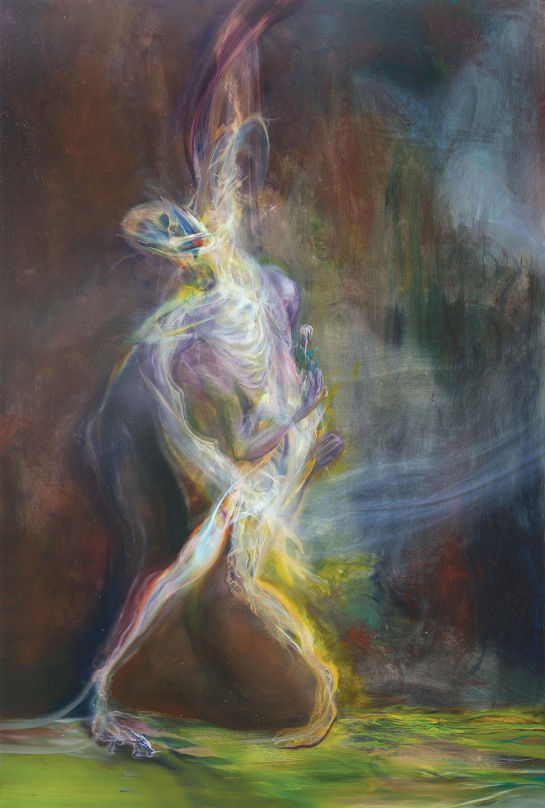

If price point establishes the value of art, it goes without saying that the auction became a central piece into the narrative of the artists, and the price reached by artists are more known to a general art public than you might expect. In the West, having young artists going to auctions is still a limited phenomenon. In Southeast Asia it is almost the norm. Some young artists don’t even transit by galleries, but go straight to auctions. A case in point has been the super sale in 2015 of a work by Ruben Pang. The auction was part of Christie’s season, which consisted of between 35 and 45 works of Singaporean artists through its Asian 20th century art sale and Asian contemporary art sale. These platforms have allowed Singaporean works to catch the attention of international collectors. During this auction, Ruben’s work ‘Light the Caretaker’, realized in 2015, was sold at Christie’s for HK$ 187.500, roughly equivalent to 22.275 euro. Many were worried about such a young artist going to auctions at such a young age. The problem is the unsustainable price level that positioned him in a way that it’s difficult to step out from. About this sale, Ruben said to the Strait Times that “That doesn’t change the way we do as artists – to work hard, be observant and have only works that we are proud to leave in the studio.” Furthermore, this sale shapes young artists’ imaginary – for better or for worse, this event is now a mark in the artist’s career.