THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 4

Ho Tzu Nyen: representing the global collective imaginary

There are artists who make objects, and are pretty damn good at their craft. Then there are artists whose production allow them to live and work in the art system. There are also artists whose work is autobiographical and very much tied to their lives. And finally, there are artists whose art is a direct continuation of their philosophical grasp on the world. Technique for them is an extension of their thought.

Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen belongs to the latter category. In his first solo exhibition in Berlin at the gallery Michael Janssen called “No Man II”, he presented a new multimedia installation. This whimsical, interactive, compelling, yet mysterious work looks like a museum of popular imagination of the human figure. We can find here clichéd representation from pop culture, from American soldiers, to characters similar to the movie Tron, all the way to mythology.

One minute into our interview and Ho Tzu Nyen had already come up with an observation which revealed the underlying conception of his entire oeuvre: “It’s always difficult to talk about the genesis of something without fictionalising it.” In answering what compelled him to create No Man II, Ho Tzu Nyen revealed how well aware he is that everything is a story. And this realisation didn’t make him disillusioned, but willing to play with it.

The artist makes the history of his creation start from a double inspiration. One is a poem of John Donne, who the artist came in contact with as a student. He drew from the Meditation XVII of the collection: “Devotions upon Emergent Occasions”, changing one single line:

“No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece

of the continent,

a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea,

Malaya is the less,

as well as if a promontory were,

as well as any manner of thy friends

or of thine own were;

any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

it tolls for thee.”

“I reproduced the John Donne poem almost entirely, except I made one small change to his text. The original text has a reference to Europe, which is saying that no man is an island. He was referring to England and he was saying that when a man dies, it’s a part of England that is washed away. I changed the world Europe to Malaya, the old name during colonial period of describing Singapore and Malaysia together. It was when Singapore was kicked out the Malays federation that our two countries split up and Singapore became what it is today. Singapore is of course also an island like Great Britain. This work has to do with this kind of global imagination.”

No Man II is a continuation of your work No Man, which you first showed it in Singapore. In No Man II, one could relate the diversity of all of these characters to the ethnic diversity of Singapore as well. Does showing it in Berlin allowed it to take on a different meaning?

All together we had 50 of these figures, because the work was commissioned for the 50th anniversary of Singapore. The Singapore version was 60 minutes long with six screens, six mirrors. There each figure was in isolation and didn’t overlap with others, so they existed in this black space, an empty place. The figures don’t have any narrative connection; they don’t speak to each other or relate to each other. However, watching the work for a long time, the figures can interact through gestures, and by light, while one figure appeared and others faded. It was almost a theatrical stage. This relation became more intense with No Man II. Here we have a foreground and a background, with group of figures that can appear or disappear in these two plans. The Berlin version is six hours long.

The video installation is interactive. Can you describe how it worked?

We projected the work on a two-way mirror – the kind of mirrors used in the interrogation rooms of police stations. By controlling the lights, you can turn it from a mirror into a glass, so it could capture the audience’s reflections amongst the 50 projected figures at particular moments.

Another thread that went into the work was your experience in working with computer graphics and 3D animation. Why did you decide to use computer-generated figures?

I found a website where thousands of different digital figures could be purchased and customised. They were used mainly by people making computer games or perhaps digital pornography. These hollow shells attracted me immediately. I thought of this website as a compendium of human figural types by the video-gamer generation. The figures on it spanning from human stereotypes to mythical and pop cultural archetypes.

Later, I found another website that offered a library of human motions, translated into data, that you can purchase. I saw this as a museum of human movements – each with its own historicity. For example, there were break-dance movements and also the movements of zombies, walking, bitting, raising themselves from the ground – all of which have become familiar to us after the zombie craze of the last decade. I began to insert these distinctive movements into digital shells that have no apparent correlation, for example, the movement of a zombie into an android, or into the digital shell of a human child. For me, No Man is made up of a gathering of figures that are not only cut off from each other, but also alienated. And then, I guess the magic is the music in the installation, and with the work unfolding in time, relationships begin to generate almost spontaneously out of the characters’ mutual interactions.

Which comes first, the music or the visuals?

What comes first for me is usually a sensation, or a state of intensity. I can’t explain it completely, but it is something that crystallizes not only image, sound, but also an idea. Everything is simultaneous. In any case, music and sound have always been as important as the visual for me. For the two versions of the piece, my few instructions to the excellent musician (Vindicatrix) was that the dynamic range of the spans from a solitary and fragile voice to a massive choir. In the end he worked with both a range of vocalists and singers, but also went to a pub and would buy them a drink and get people to sing. So that’s how we created this massive crop of voices in some parts of the work.

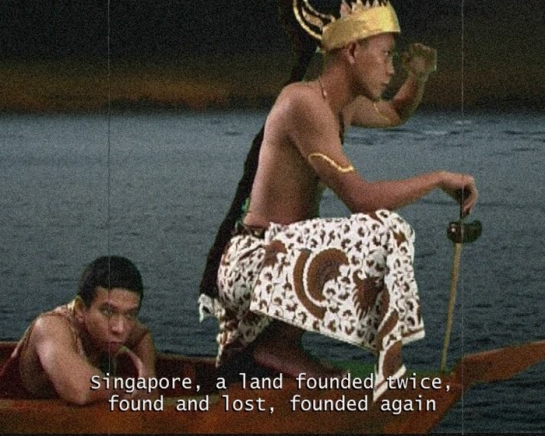

We can find this blend of both real and mythological figures from the past also in one of your most celebrated works: Utama – Every Name in History Is I, about the narrative of Singapore. That 2003 video piece is a seminal work in the contemporary art history of Singapore, and is now showcased in the National Gallery of Singapore. You often pointed out how historical and mythological figures serve a need for the present, in contemporary times. How was this idea articulated in Utama, versus No Man II?

A lot of the works I’m doing today have lines or threads that came from Utama. Compared to No Man II Utama might seem to have a direct relationship to Singaporean history, whereas No Man II seems to stem from this more undefined, global imaginary. But the narrative of Utama, was precisely that of a single figure exploding into numerous ones, Utama becoming “every name in history”, from Vasco de Gama to Christopher Columbus to Alexander the Great, to Actaeon the Hunter of Greek mythology. This parade of characters and the hollowness of the figures can also be found in No Man II. Both works evoke a certain kind of emptiness.

By emptiness, do you mean a gap in history, a myth or a narrative that those characters try to fill?

For me, emptiness is simply the space of latent possibilities. And gaps are spaces that allow for movement. Maybe this is why I think of the actors in my works as empty channels. That’s why I work with non-actors, because they are more blank. They don’t act, they don’t dramatise. Things pass through them.

Your interest for history doesn’t appear only in your work, but also you did a TV documentary ‘4 x 4’ of four episodes on Singaporean artists, and you even compiled a dictionary of the history of southeast Asia for the Asia Art Archive. I see this active role you take in documenting and reflecting on the art history of Singapore and Southeast Asia. I’m wondering why are you taking this responsibility not limiting yourself to being an observer of sorts.

For me, making art and reflecting on these questions is the same thing. I can’t see how interesting art can be produced without some sort of reflection, and how creative reflection can be performed without artistic transformation. For me, the best art writing transforms the art objects they engage with, and the best artworks transform the meaning of the art that has come before it.

Perhaps my thinking has something to do with coming from Singapore, and starting my practice at a time when we did not have a lot of good art writing, and what little of it we had was not widely circulated.

I guess this context in some way sparked the seeds of ‘4 x 4’, in which I wanted to combine some of the art historical insights of writers I enjoyed, argue with them a little, while reconstructing four artworks by four artists I admired, while making something that confused the borders between television, film, contemporary art and writing, and I wanted to circulate this to the widest audience possible then, which was television.

You mentioned most of your inspiration comes from reading, which is a solitary activity. But this then becomes collective through the process and the themes that you represent.

Reading appears solitary but actually, it is the surest way to be in glorious company. Reading a book is already to be in the presence of its author. Moreover, every book, and every author is always already tied to the literature that came before it, just like every philosophical book is always already engaged with a number of other philosophical traditions. When you open a book, you are always already with a multiplicity of others.