THE SINGAPORE SERIES – CHAPTER 3

Boedi Widjaja: the idea of place

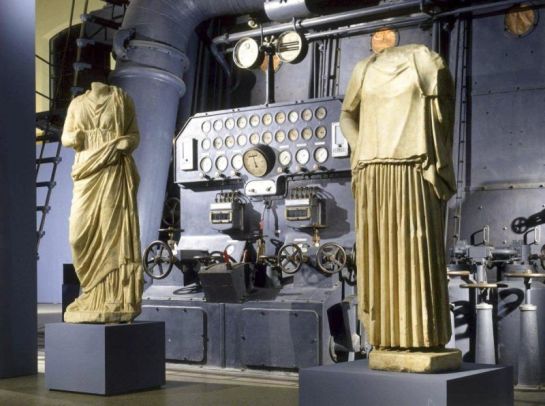

What is a place? How do you feel connected to a place? Since moving from Singapore to Indonesia at age nine, artist Boedi Widjaja kept on asking himself these questions. My first encounter with Boedi Widjaja’s work happened in Rome. It was the day after the opening night of the 2012 Premio Celeste, an international prize dedicated to showcasing young talents from all countries. The building where the award ceremony happened was interesting in itself. A former power plant, the Centrale Montemartini was a unique example of industrial archaeology turned into a museum of classical statuary. The contrast couldn’t be any starker. Among the black steel levers, timers and dark machines, white marble statues emerged. The immaculate splendour of ancient Greek and Roman bust of Dyonisus and Apollo were juxtaposed to the steamy image of progress in the industrial age.

Conversely, the room where the winners of the Celeste Prize were showcased was bare, to give emphasis to the contemporary works. It was Boedi Widjaja’s piece called “Ian, Rem, Kal” that caught my eye. The work consisted of three couples of frames. Each couple had a realistic pencil portrait of a person in one frame, and a silhouette of a building in the other. When I finally recognized who the characters were, I was amused by the commingling of personalities belonging universes apart: Ian Curtis, Rem Koolhaas, Kal El – commonly known as Superman. In Boedi’s vision, these were “involuntary separatists”, creating fractures on different levels of existence. Curtis’s tortured life leading to his suicide represented an emotional and personal fracture, seen as irrational as the level on which music operates. Koolhaas’s abandonment of poetic space and departure from designing interiors to large-scale city planning was a disruption the conventional fabric of the cities (and he had a lot to say about it in his book “Singapore Songlines”). On the other hand, Superman’s rupture consisted of being a superhuman from an alien planet, struggling to be accepted on earth. I looked at the silhouette of buildings associated with each one of the three figures and tried to draw a connection. Ian, Rem, Kal were related to building that had meaning for them. For Ian, it was the Manchester nightclub The Hacienda, where the Joy Division used to regularly play their gigs. For Rem it was his iconic CCTV tower. For Kal it was The Fortress of Solitude, a place of solace and occasional headquarters for the DC Comics hero. “Ian, Rem, Kal” was an early meditation on the meaning of places and identification with space.

When Boedi Widjaja and I sat to talk about that work a few years later, he confessed his pride to have brought that particular work to Rome. “Rome is really a showcase of architecture, with some of the most wonderful buildings in the world. To show a work related to the city and the architecture was pretty awesome for me!” Boedi was trained as an architect in Sydney and this influenced his thinking and forfeited ideas about how you think about space, not only in terms of square meters, but also in a philosophical sense. I asked him if western art history was a point of reference for him at all. Or did if he looked more at the interpretation of it by the early contemporary artists in Singapore? Not surprisingly, Boedi argued that his primary point of reference primarily was not art history. Like the majority of contemporary artists working in today’s interconnected and cross-breed world, his first inspiration was contemporary culture, fuelled by personal experiences. The artist ascribed this attitude also to the fact that he never went through the academy: “I spent ten years running a design company with my wife, before practicing as a visual artist. I draw a lot from personal experiences and I naturally reference issues like migration, displacement, diaspora, travel and isolation, because of my childhood experiences.”

Boedi grew up in a traditional family in Solo, Indonesia. For his generation (class of 1975) the usual expectation was for children to do well in education and later on become professionals with a stable income. “The idea of becoming an artist never crossed my mind.”

Boedi’s childhood saw indeed his migration from his native Solo to Singapore, due to the tensions the Suharto regime which targeted Chinese-Indonesians.

“This made you not simply an Indonesian moving to Singapore, but it forced you to acknowledge your Chinese heritage. It’s almost a triple relationship with the idea of home”, I observed.

“When I was growing up, I was influenced by the fact that my father belonged to the generation that had cultural historical connections to China. My father was born in Indonesia, but received Chinese education in Indonesia before the Chinese schools were closed by Suharto. In his generation, many desired to go back to the homeland. In fact, one of my uncles did so and I think he regretted it. I think I must have received this strong sense of nationalism from my family.

The second reason has to do with my perception of the feeling of being excluded from the Indonesian national identity because of my ethnicity. Because of it, I had to leave home, I had to leave my family, my parents and I lost all my school friends. I couldn’t grow up in Indonesia. Over the years I started asking myself, am I really Indonesian or not? So I think that’s why national identity is something very complicated for me. I think on one hand I understood I shouldn’t get to fixated with the definition of home. On the other hand, there have been always deeply entrenched emotions related to the idea of home I grew up with.”

The seed for what would became Boedi’s main thread of research started in 2010, and was planted by a collective project involving three other artists (June Yap from Singapore, Taisuke Koyama from Japan and David Letellier from France) called “INSITU.ASIA”. The idea for the project came to the artist while he was watching an interview with Jeff Koons on YouTube. The American artist defined an artwork as a transponder towards the art experience that happens within the viewer. “In short, the work itself is not the art; it is the resonance felt by a viewer that is art.” While Boedi has never been a fan of Koons, the statement fixated in his mind. “It was liberating for me to know that art already existed in each one of us, it felt great to see art from this point of view: that something so beautiful, fragile, intense and full of wonder – something I used to imagine as elusive from most of us, is actually at a fingertip.”

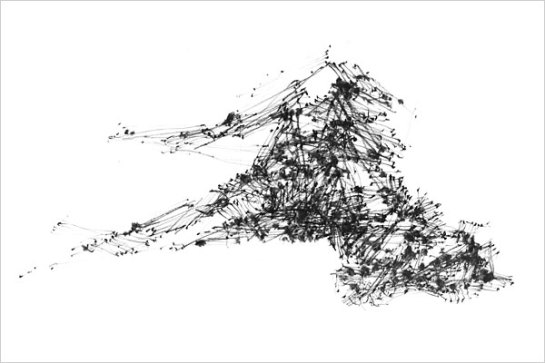

Indeed, the project INSITU emphasised the attention on the physical interactions with the environment. The artists spent a bit of time in each place depicted and explored the stories and the complex layers of culture of those particular places. Then they went back to their studio and reworked that brief encounter through their memory. The suggestions were elaborated in the form of installation, video performance and photography. “At the time, we were calling them ‘artist maps’. The project was about creating meaning and art through your experience. It was about what you made in that encounter.” The physical space was reimagined by the artists, and the memory encapsulated into an object, an artwork.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but looking back it relates to that sense of displacement that I felt. The fact that I couldn’t quite connect to Singapore when I was growing up. That the ground wasn’t the home I came from. It was so strong as a child.”

But then, in late 2011 – at a time of charged national conversation on the rights of immigrants in Singapore – Boedi finally got his Singapore citizenship and in early 2012 he participated to the formal ceremony. Without knowing it, that event was the trigger for his biggest body of work. “I was really looking forward to the day, because I though about the change in citizenship for a very long time. I grew up here, but I could never decide whether I should retain my Indonesian citizenship. I continued to feel very deeply for Indonesia, the land, the country, the people. But the memories I had growing up were all in Singapore.” He pondered the decision for almost ten years and finally decided that Singapore was really the home that he wanted to root himself in. “When I went up onto the stage to accept the identity card, I was thinking: ok, I’m going to feel very much at home now.” In a very Singaporean way, he assumed that bureaucracy would have fixed emotional matters. Of course this didn’t happen. “What happened instead is that I felt even more like a foreigner. This surprised and disappointed me. Then I slowly realized that if you want to feel at home in a place, you have to have memories of being at home in that place. I had indentified myself as a foreigner. Singapore had represented to me a place of being away from my childhood home. So art for me became like a process of bringing these deeply entrenched childhood memories into the present, to draw different sets of circumstances into the present.”

“Today I have a family of my own. I have a daughter in Singapore and over many years I have formed relationships and friendships in this city. I wanted to bridge those elements with my childhood memories to feel more and more at home and rooted in this place.” That’s how his series “Path” started. From throwing graphite-coated balls on paper-lined walls to physically dragging doors through neighbourhoods, there is no constant in the series, neither in terms of medium nor in terms of concept. There is only a spasmodic willingness to find a bridge that would connect people to places. The artist describes the series as personal and social, factual and imaginative at once. “The works were also transformational, helping me root for the future through a recasting of the past.”

Italian songwriter De Andrè used to say that we generally have only one single great idea, and we keep on reworking that throughout our entire creative life. I’d add to that, to try to define this idea in words is nearly impossible, especially if this is an emotional condition more than a theoretical idea. The moment you catch it, it wouldn’t make sense to try to express it through art. Boedi Widjaja has reflected on the feeling of place, belonging and homeland from so many different perspective and moments so that it is possible to trace an evolution of the idea over time. In his 2016 show “Imaginary homeland” at Objectifs, Singapore, he arrived at the conclusion that places exist first and foremost in our imagination.

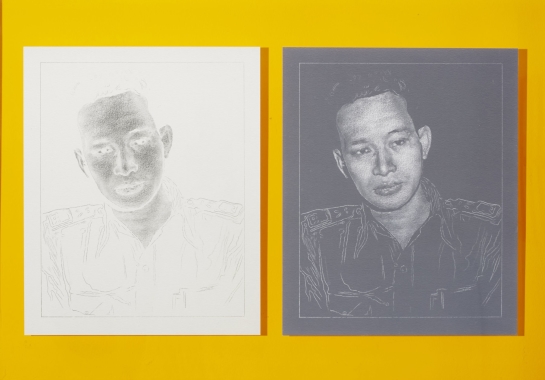

“Imaginary Homeland” takes on the public imaginary of Indonesia. The memories shared by an entire nation end up informing the action and identity of the individual. On a cultural level, they impact people’s remembering and creating personal narratives. The imaginary that Boedi decides to reference is political, drawing from a moment in history pivotal for determining the post-colonial identity of Indonesia. This is the mid-sixties, a period of transition from the government of Sukarno, the charismatic socialist leader who gained independence from the Dutch Colonials, and the rise of general Suharto, the bloody dictator who opened up Indonesia to the free market and determined its economical growth. The images are black and white reportage photographs of Indonesian politicians printed in negative and re-drawn by the artist. The act of drawing realistically is by itself an act of remembering, an act which took place during time-demanding sessions of realistic drawings. But that is not all there is to the work. Viewers are also called to participate by using their mobile device, with inverted settings turned on, to see the positive image. This bouncing between the artist’s introverted immersion into himself and a willingness to draw the spectator in, is a constant in Boedi’s art practice. As if only together we could make sense of our collective memories; what is called the imaginary. “Imaginary homeland has to do with how national identity became a very prominent way for me to identify where home was” he explains. In this sense, home doesn’t describe so much a place, but it describes your relationship with that place. “It’s like how the word marriage describes your relationship with another person. Home doesn’t have to be exclusively about national identity.”

Today, thanks also to his practice, Boedi has found a sort of harmony in inhabiting multiple cultural identities – a characteristic that he foresee as being increasingly marked in the future. “It is like a diagram. I feel all these places are part of a network of relationships and my identity is found in the act of moving between these points in the network. This constant moving is something that today I accept and enjoy.”

Boedi Widjaja’s story can be seen as peculiar, except that it is not. We will see later how Singapore’s story has been first and foremost a story migration. In that the Lion City offers an amplification of certain dynamics which are becoming the norm all over the world. In a time of massive global migration – as I’m writing, the European refugee crisis is very much an international priority – and as the world is becoming more and more interconnected, the coexistence of multiple national and cultural identities into a single individual is becoming commonplace. We feel it is the start of a new era where national identities are becoming obsolete. In reality, what we are witnessing is either a strengthening of these – in a wave of conservative nationalism – or a celebration of a boundless world without categories. Aside from the fact that this won’t necessarily be desirable, it is also structurally harder to achieve in today’s world where market and bureaucracy create a deadly tangle. I will talk about this specific issue later in the Bureaucracy/Imagination chapter.

One thing is for sure: the concept of nation is not something we will get rid of any time soon. If Boedi is looking from Singapore to Indonesia, Singapore is very keen to build its own imaginary thanks to a top-notch army of trained artists from Indonesia and the region at large. In a way, Singapore has understood that the key is to make national identity fluid. The Lion city is particularly suitable to achieve this, given its nature as a city port. Artists like Boedi Widjaja don’t just help themselves in producing work dealing with a very modern form of cultural alienation, they are also signalling their presence and return to art the role of comforting the disturbed and disturbing the comfortable. In addition, artists dismantle conventions, allowing us to see what is underlying. They recover our metaphysical thinking – in an ideal platonic dimension where the ideas are not hard and defined as the Greek philosopher saw them, but rather morphing and fluid. Starting from the minimal units, we can assemble them together to form new categories more relevant to our times. Art helps us get straight into the primal questions about place, time, space and ourselves. Our coordinates.